Smoke but no fire in nuclear news from India

Really very little has changed

By Dan Yurman

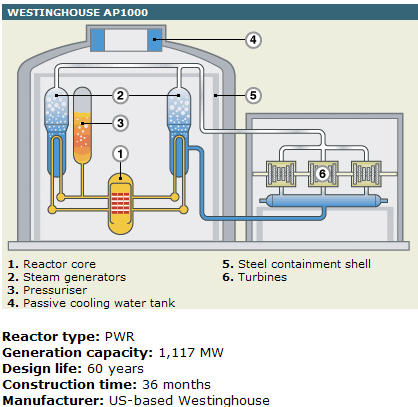

A flurry of media stories last week about Westinghouse having a nuclear reactor deal at Gujarat is insubstantial proof that there is any change in opportunities for American firms to enter India's energy markets. Things got rolling with a press release on June 13 from Westinghouse that it had agreed to negotiate an "Early Works Agreement" supporting construction of up to six 1,150-MW AP1000 nuclear reactors at the Mithivirdi site in Gujarat. Work scope includes preliminary licensing and site development activities.

Separately, Areva announced last week it would sign a contract by December to build the first two of six planned 1,650-MW EPR reactors for Nuclear Power Company of India Ltd. (NPCIL) at Jaitapur in Maharashtra.

Then on June 15 in Washington, D.C., with Indian Foreign Minister S.M. Krishna standing next to U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, the media headlines followed saying that the AP1000 deal represents "a significant step toward the fulfillment of the landmark U.S. India agreement."

Under questioning from the DC press corps, Clinton acknowledged that "there was still a lot of work to be done."

The sticking point, which has been evident all along, is India's nuclear liability law that was passed by parliament in 2010. Its assignment of supplier liability, long after components have been installed and are operating in a plant, creates unreasonable risks for U.S. firms. Really nothing has changed because it is politically impossible for Indian Prime Minister Singh to revise the liability law.

India has signed the IAEA Convention on Supplementary Compensation for Nuclear Damage, but the international agreement is not in force for diplomatic and legal reasons. The U.S. government has since complained that India's nuclear liability law is not compliant with the IAEA convention. The U.S. is said to have held its fire on further criticism of the Indian statute in hopes that implementation measures domestically can be developed that will open the door to U.S. firms. Sequestering U.S. built reactors in NPCIL special "nuclear parks" may be part of the answer.

Westinghouse dreams of success at Gujarat

On June 13, Westinghouse and NPCIL signed a memorandum of understanding that sets up a process to negotiate an Early Works Agreement supporting future construction of multiple 1,150-MW AP1000 nuclear reactors at the Mithivirdi site in Gujarat. The statement goes on to say that the agreement will include licensing and site development work.

Westinghouse spokesman Scott Shaw told the Pittsburgh Tribune that work could begin as early as this fall. He also cautioned, however, that the U.S. and Indian governments must address the current supplier liability law that is an impediment to an agreement to build a nuclear reactor. As a result, this agreement cannot be interpreted as a deal to deliver a reactor.

The announcement got a fair amount of press coverage in the U.S. and India. Anyone who has followed development of India's nuclear program, however, knows that some of the pieces are already in place. The site in Gujarat has been on NPCIL's list for some time, with the process of acquiring the land for the reactor started last March.

The announcement, however positive it may sound, is, in effect, an agreement to develop an agreement. It is not a breakthrough in the civil liability law impasse. It could be at least a decade before a U.S.-made reactor powers the Indian electrical grid.

While Westinghouse was promoting its latest dialog with NPCIL, G.E. Hitachi (GEH) told Platts on June 13 that it was also negotiating a similar Early Works Agreement with NPCIL for a nuclear plant near Kovvada in Andhra Praqdesh. GEH said that the site would eventually host six of its 1,500-MW ESBWR reactors. Like the Westinghouse announcement, this one has been in the works for a while. One change is the reference to the larger ESBWR rather than the 1,350-MW ABWR that G.E. Hitachi has built for other customers.

The Westinghouse reactor received its safety certification from the NRC in December 2011. The ESBWR is still in the process of completing that milestone. The Areva EPR is also in the process of fulfilling the requirements for NRC safety certification. The NRC regularly updates the schedule for projected completion of these activities. Other nations look to the NRC review as a de facto "gold standard" for review which is why it is so important to vendors.

Areva advances at Jaitapur

French state-owned nuclear giant Areva said on June 14 that it hopes to sign a contract in December for two of a planned six pack of 1,600-MW EPR nuclear reactors to be built at Jaitapur in Maharashtra on India's western coastline. It has been the site of contentious anti-nuclear demonstrations, but not solely over safety issues. Displaced farmers are demanding supplemental compensation for being relocated from the reactor site. The government has promised to address their claims.

Arthur Montalembert, the head of Areva's Indian operations, told financial wire services that if the contract is signed by the end of 2012, the first reactor could enter revenue service as soon as 2020 and the second one a year later.

Areva itself is unlikely to provide the capital to build the plant. Montalembert said that the firm would approach French banks for financing. Last December, Areva slashed capital spending as part of a global review of its commitments in various markets, most notably in uranium enrichment.

India's nuclear market reconsidered

India does a lot to promote new nuclear construction. The government buys the land, does the initial site environmental assessments, and prepares the site for construction. Once a plant is built, the reactor operator sells electricity to NPCIL at government rates and not market-driven prices relative to other fuels, e.g., coal. That said, NPCIL also manages all aspects of nuclear plant development and determines the allocation of electricity in each state.

Between now and 2022, India plans to build 39 reactors for a total of 45 Gwe. U.S. firms may wind up building about 10-12 GWe of the market in that timeframe as part of India's massive new build.

The market will be divided up between U.S. firms, Areva, Russia's Rosatom, and India's drive to technology self-sufficiency with a 700-MW PHWR. Also, India claims it will start work in 2013 on two 500-MW fast reactors.

There are conflicting reports that India's targets by 2022 have been reduced to as little as 14 Gwe. The economy is slowing down. India's bureaucratic government, endemic corruption, and localized opposition could present huge frustrations, and costs, to American firms. Whether the market share they seek will be worth the price remains to be seen.

______________

Dan Yurman publishes Idaho Samizdat, a blog about nuclear energy and is a frequent contributor to ANS Nuclear Cafe

# # #