Thoughts on THRESHER

As is the case on every 10APR, I find myself – even in the midst of the present national and, really, worldwide crisis – returning to thoughts of the USS THRESHER on this date in 1963. All of us who have been through the Naval Nuclear Power Program and served in submarines are aware to greater or lesser extent what happened; my experience, having served aboard one of the SUBSAFE boats whose development was a direct result of the accident, lends perhaps to more sustained reflection.

As is the case on every 10APR, I find myself – even in the midst of the present national and, really, worldwide crisis – returning to thoughts of the USS THRESHER on this date in 1963. All of us who have been through the Naval Nuclear Power Program and served in submarines are aware to greater or lesser extent what happened; my experience, having served aboard one of the SUBSAFE boats whose development was a direct result of the accident, lends perhaps to more sustained reflection.

Loss of THRESHER

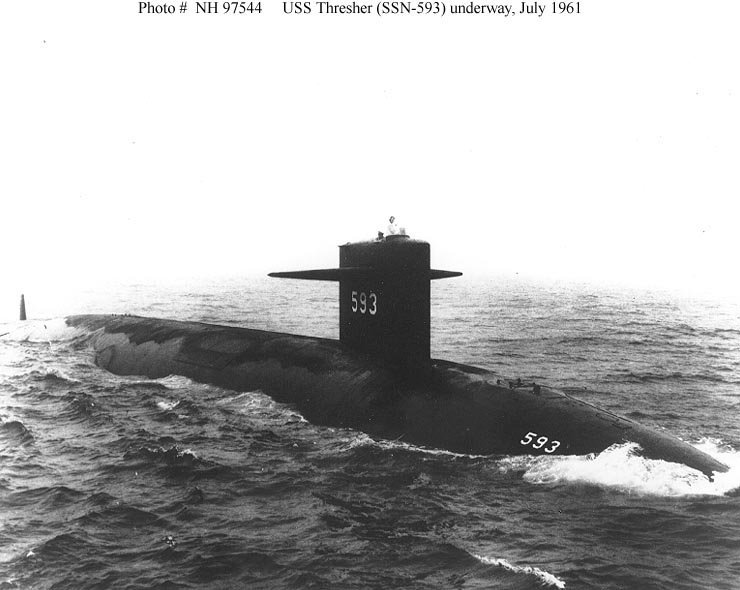

The events of that day in 1963 are essentially these: USS THRESHER, the first of a new class of deep-diving submarines (and really, a wholly new weapon just as had been USS NAUTILUS) had already been in service for some time and in fact, had been through an extended shipyard period for considerable work. New sea trials were needed to effectively recertify THRESHER. The boat (we called them “boats” when I was in) was conducting what we call a “deep dive” or a dive down to test depth – that’s the deepest depth at which a submarine is designed to operate. Somewhat below that is collapse depth, which is the depth at which the pressure hull is expected to fail.

As the boat dove for that last time, USS SKYLARK, the escorting surface ship for the mission, maintained contact on the then-used underwater telephone that allowed voice communication through the water. THRESHER reported that it was commencing its deep dive test just after 7:45 AM that morning, and for an hour and a half nothing seemed out of the ordinary as THRESHER snuck down to her test depth. However, at 9:13 AM SKYLARK received a transmission from THRESHER:

“Experiencing minor difficulties. Have positive up angle. Am attempting to blow. Will keep you informed.”

The sound of compressed air was heard over the phone next, surely the first attempt to blow the main ballast tanks – which immediately became impossible as the lines froze, as later testing on other identical boats would prove. At 9:16 AM SKYLARK heard a garbled message relating to test depth, and shortly another very garbled message containing the number 900 – possibly, a reference to exceeding test depth by 900 feet. At 9:18 AM, 10 April 1963, SKYLARK sonar operators clearly heard a violent underwater burst or explosion which was immediately recognized as an implosion. USS THRESHER had been lost with 129 souls on board.

Thoughts Today

The only thing of which we can be certain was already augured during hearings before the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy in 1964 – that we will never know exactly what was transpiring on board during those last moments. Various theories have emerged, either including or supposedly ruling out flooding (inrush of seawater from a failed pipe exposed to sea pressure, spraying equipment, weighing down the boat, and causing associated system failures.) It is obvious something was happening that caused the Captain to blow the main ballast tanks, but what was happening exactly and what the Captain knew about what was happening from the control room is impossible to know.

Much effort went into trying to figure out what MIGHT have happened – a huge gamble in many ways since no one knew what to fix. Worse, many submarines had been ordered to roughly the same design and a number of similarly equipped ballistic missile subs was also on the way. A number of observations, relevant today to any nuclear or for that matter industrial enterprise came out and were published at various points in the Congressional record. I’d like to close today by offering some of these points as things to think about.

•Admiral Rickover had a number of silver-brazed seawater and other piping system joints examined on THRESHER and found an alarming number unacceptable; he told the JCAE in 1964 that THRESHER might have gone to sea with hundreds of substandard joints over which he had no jurisdiction. His remarks to the JCAE pointed up a continued substandard performance by shipyard workers who now worked in an industry in which zero error was permissible. Changing standards over time as nuclear subs became the norm (over diesel subs) and modulating requirements had thus caught up to and then exceeded the professional standards and capabilities of many shipyard workers whose standards had stood still.

•Rickover had tried to push hard with NAUTILUS and then again with THRESHER to get those in charge, namely the Bureau of Ships, as well as everyone else to understand that each of these evolutionary steps was a wholly new weapon and not just a regular boat with a nuclear powered back end. One Senator remarked during hearings that he’d long ago seen a newfangled “horseless carriage” which was little more than a buggy with a gasoline engine fitted and wondered if the Navy wasn’t doing the same sort of bungled approach with nuclear submarines. Game-changing innovations require top to bottom reassessment of entire platforms. Failure to grasp this had caused the Navy much headache post-NAUTILUS and had apparently now lost them an entire crew (and a group of civilian technicians riding THRESHER to check out contracted systems.)

•The rapid multiplication of nuclear submarines as had been ordered by the Executive Branch and approved by Congress was not leading to a rapid improvement in construction skills; instead, it was leading to a rapid intensification of problems with individual boats that could not be fixed by simply enforcing present standards. A new overall and somewhat heavy-handed approach would be needed to hammer home the requirements for each and every weld, every bolt, every component that could affect a boat’s watertight integrity. This was the spark of what became SUBSAFE – which is the most successful Navy quality program that should never have had to happen in the first place. We may all have heard someone say something along the lines of “well they don’t put those gates and signals at a railroad crossing until someone gets killed there” which, in fact, is not true, but we do all realize that sometimes a massive shakeup is required to get attention and refocus priorities. In the Navy’s new nuclear submarine program, which it SHOULD have recognized as a wholly new venture, the loss of the THRESHER was its own “Three Mile Island” moment. Rapidly expanding programs will exacerbate, rather than somehow inherently improve, lack of talent and adherence to standards – a problem the Navy fixed. Other various industrial programs have, and have not, responded to their “TMI” or “THRESHER” moments as well.

So, as I sit here today thinking and, for once, writing publicly about the loss of THRESHER all those years ago I wonder in today’s Navy how much the young sailors know today, all these years later, about THRESHER I would have to imagine, given the exemplary record since (one further nuclear boat, USS SCORPION, lost to an operational accident in 1968 and one serious fire on the diesel-powered USS BONEFISH in the 1980s) that the loss of THRESHER and her fine crew has not been entirely in vain. It is important that the crew of THRESHER is remembered, but perhaps it’s even more important that it never happens again.

Will Davis has been a member of the Board of Directors for the N/S Savannah Association, Inc. He has been a contributing author for Fuel Cycle Week, and wrote his own popular blog Atomic Power Review. Davis is also a consultant and writer for the American Nuclear Society, and serves as Vice Chair of ANS’ Book Publishing Committee. He is a former U.S. Navy reactor operator and served on SSBN-641, USS Simon Bolivar. His popular Twitter account, @atomicnews is mostly devoted to nuclear energy. He likes to collect typewriters and early pocket calculators, which are piling up.