Army Off-Road Nuclear Train – 1958

At the end of the 1950’s the US Army was looking at its entire operational sphere to determine in what areas nuclear energy could be of benefit. While many of these are fairly well known today – for example, the small nuclear plants that were to have been installed at remote locations for powering bases like the Defense Early Warning stations – there are a few applications that remain obscure.

The booklet seen here, “Army Nuclear Power Program,” was given out as a part of the Associate Engineer Officers Course at The Engineer School, Fort Belvoir, Virginia as a complement to a presentation delivered by Major James T. White, Office, Special Assistant for Nuclear Power, which was itself a part of the Office, Chief of Engineers (US Army Corps of Engineers.) The presentation was given on April 22, 1958.

The booklet seen here, “Army Nuclear Power Program,” was given out as a part of the Associate Engineer Officers Course at The Engineer School, Fort Belvoir, Virginia as a complement to a presentation delivered by Major James T. White, Office, Special Assistant for Nuclear Power, which was itself a part of the Office, Chief of Engineers (US Army Corps of Engineers.) The presentation was given on April 22, 1958.

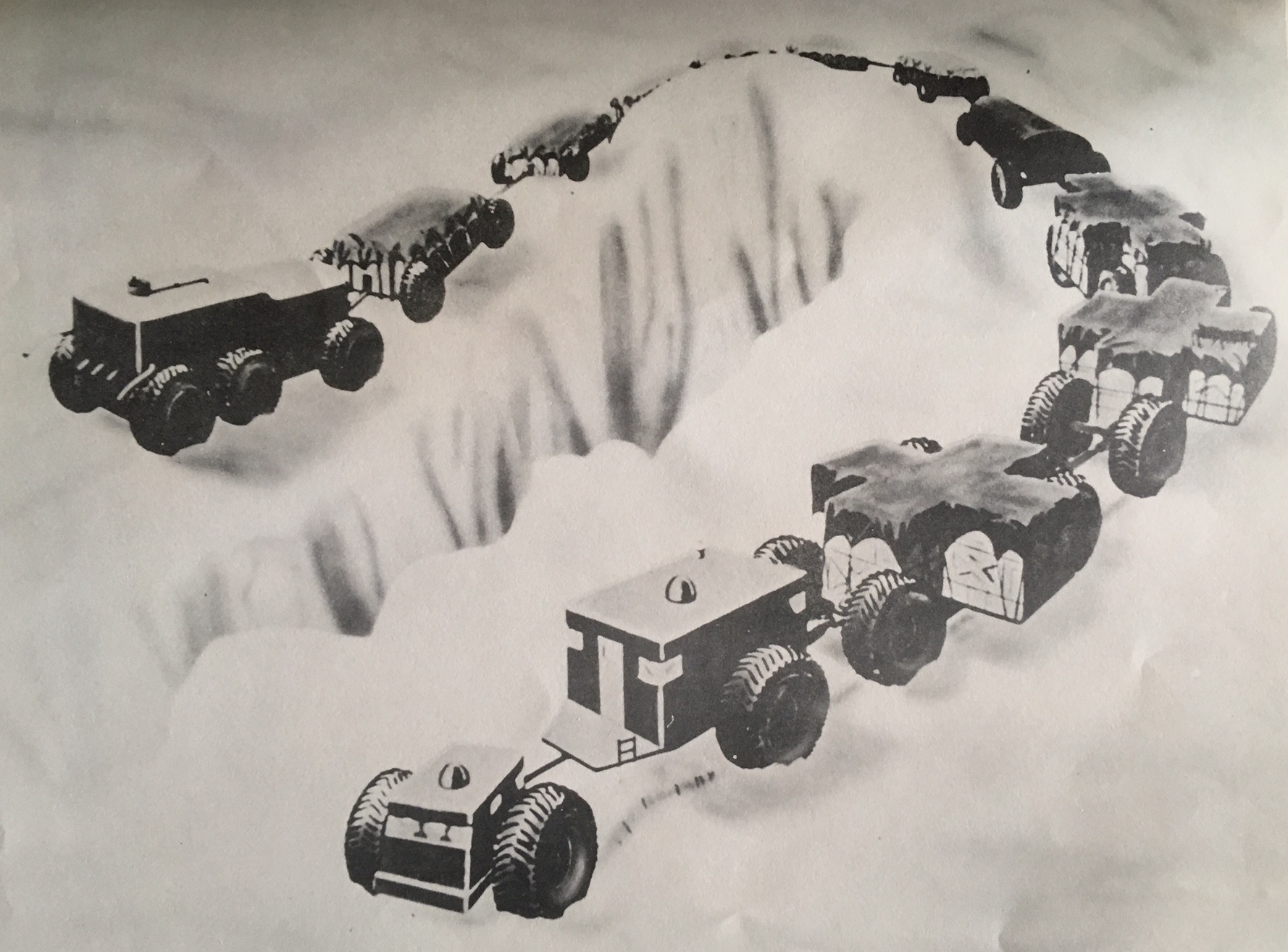

In the booklet (among many interesting things) is the mention of a peculiar concept of transportation – an “off road train.” Some description here is required.

The Army was responsible for operating many far-flung bases, some of which were sited well within very primitive and,meteorologically and climatologically, hazardous areas. The Army had to constantly transport back and forth personnel, and ship abundant supplies (in particular diesel fuel) to these various bases – a massive, and incessant, logistical consideration. Further, this kind of operation would have to be established on a massive scale in the event of actual combat, as supplies would have to be ferried from rear or landing areas to the front area. These continuous land shuttles would take up more and more fuel just to move themselves the further they stretched.

A way to alleviate at least some of the cost and complexity of this sort of operation, at least in theory, was to develop “road trains” – that is to say, a string of rubber-tired road and off-road vehicles – which would be powered by nuclear energy. The concept shown in the 1958 booklet is seen above. A diesel-powered prototype was conceived first for testing of this 12 unit transportation system, which would later be followed by a nuclear prototype. According to the booklet, though, a new reactor type would have to be developed (that is, specifically) for this sort of operation to become possible. Clearly, light weight and high power-to-weight for the developed plant would have been “musts” for the concept. It’s unclear whether the power unit (presumably at left) was to drag the procession along itself or distribute electric power throughout the train to all the wheels. It does seem as if the power unit is unmanned here; driving may have been by television from the manned units seen on the right end of this string of vehicles.

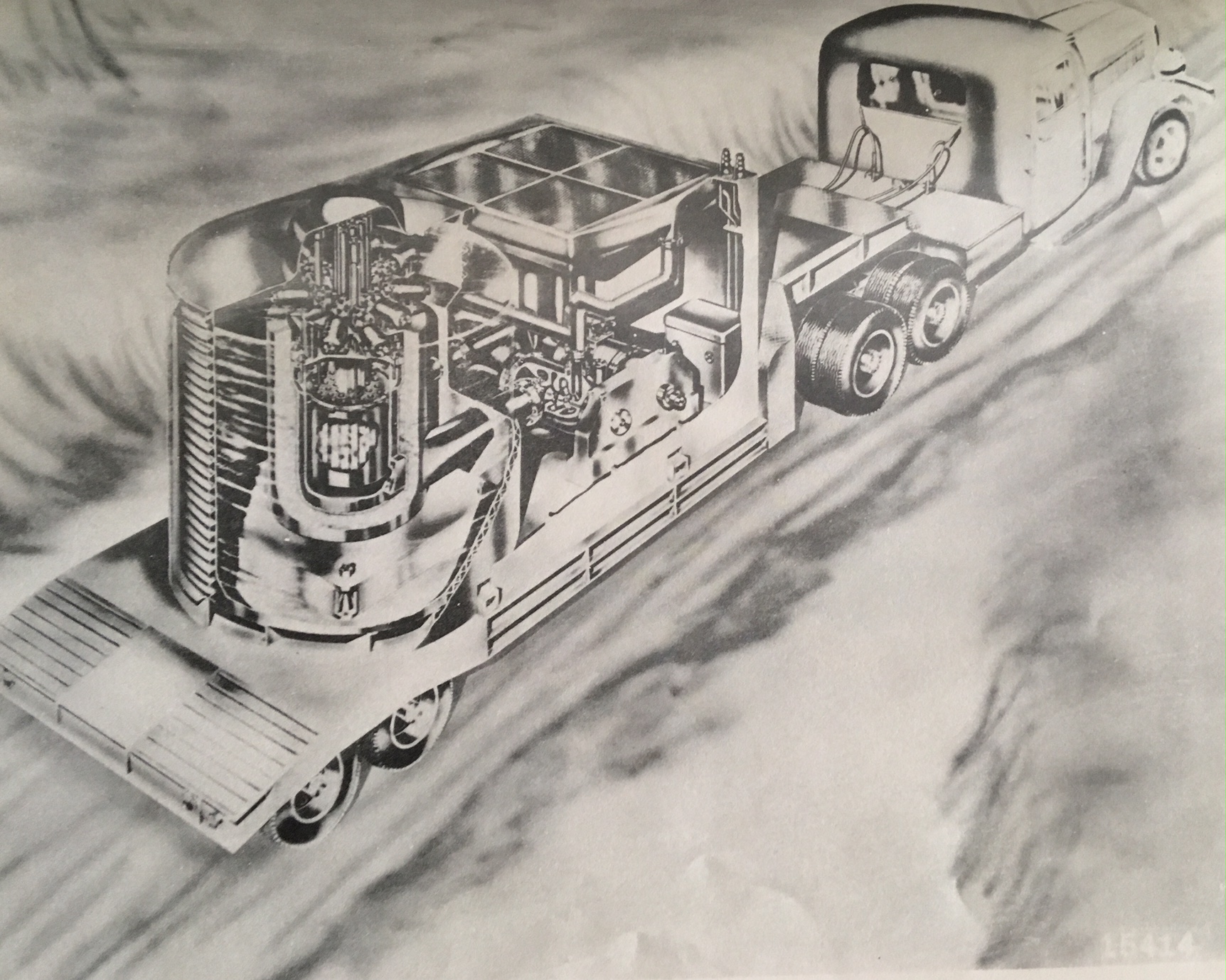

One hint at a possible development of a reactor for such a system is given in the book – the truck-mounted, and mobile, sealed gas-cooled power plant shown below, later known as ML-1.

This concept was for a compact, gas-cooled reactor power plant that was easily moved around, easily set up and taken down and which could replace mobile diesel generating units en masse. This sort of technology would have been likely considered as a power source for the off-road “trains” the Army was considering as it had all the theoretical (read as “paper reactor”) advantages necessary.

This concept was for a compact, gas-cooled reactor power plant that was easily moved around, easily set up and taken down and which could replace mobile diesel generating units en masse. This sort of technology would have been likely considered as a power source for the off-road “trains” the Army was considering as it had all the theoretical (read as “paper reactor”) advantages necessary.

There was in fact another, different Army concept for nuclear power on land but used in “trains” – tanks. At one time the Army had a concept for cutting the diesel fuel use that resulted from tanks driving from rear areas all the way up to the front lines – a nuclear mobile power station that would drive along with the tanks. Each tank – of very conventional design – was to have included an electric drive motor on its transmission and a sturdy pole on the top rear of the tank. Cables would have strung together a dozen or more tanks with the nuclear unit in the middle; the whole line would then have moved along from the rear up to relatively near the combat zone (but out of danger) where the cables would have been taken down and the tanks dispatched on their own. The power unit would then return to ferry more tanks. Obviously, this concept was fraught with problems. For example, the extremely heavy tracked power unit would not have been able to go through terrain that tanks might well have been forced to cross – and even some bridges would have been too light for it. Not surprisingly, ferrying tanks simply under their own power was found to be much better and this non-solution was never applied.

I think now, though, about the ideas of having remote areas powered by small, advanced reactors and, perhaps whimsically, think of revisiting the land-train idea. It might be one way to further augment clean energy for remote areas – get them off of fossil fuel for local power first, and then, later, with experience of advanced, compact and reliable reactors in hand, get them their supplies using nuclear energy as well. It’s an idea worth looking at – at least, on paper. One could be sure that the Army would again be interested and, hopefully, might pick up some of the bill.

Will Davis has been a member of the Board of Directors for the N/S Savannah Association, Inc. He has been a contributing author for Fuel Cycle Week, and wrote his own popular blog Atomic Power Review. Davis is also a consultant and writer for the American Nuclear Society, and serves as Vice Chair of ANS’ Book Publishing Committee. He is a former U.S. Navy reactor operator and served on SSBN-641, USS Simon Bolivar. His popular Twitter account, @atomicnews is mostly devoted to nuclear energy. He likes to collect typewriters and early pocket calculators, which are piling up.