Carving up Turkey’s nuclear energy market

The question is how big is the bird and will any of the proposed deals fly?

By Dan Yurman

Competition for Turkey's second and third nuclear power stations has heated up, but it isn't clear whether any deals will be signed soon. China, South Korea, Japan, Canada, and Russia all want to supply the plants, which are expected to be about three-to-five GWe each depending on how many reactors are built at each site.

Competition for Turkey's second and third nuclear power stations has heated up, but it isn't clear whether any deals will be signed soon. China, South Korea, Japan, Canada, and Russia all want to supply the plants, which are expected to be about three-to-five GWe each depending on how many reactors are built at each site.

Turkey's goal in pursuing a nuclear energy strategy is to gain energy independence from imported oil and natural gas and to boost export earnings through sales of electricity to other countries in the region.

The second plant is slated to be built at Sinop on Turkey's Black Sea coast. The third plant would be placed north of the Bosporus channel along the Black Sea coast, but within spitting distance, as the crow flies, of Bulgaria's border with Turkey.

Russia's contract at Akkuyu

In May 2010, Turkey signed a contract with Rosatom to build Turkey's first nuclear power site-4.8 Gwe of nuclear-powered electrical generating capacity at Akkuyu in Mersin on the country's Mediterranean coast. The deal hinged on Russia's financing and building four 1,200-MW VVER type reactors and operating them for 15 years, after which Rosatom expects to cash out to Turkish investors. The reactors are slated to be completed in 2019.

Rosatom was the sole bidder on the Akkuyu project after three western consortiums withdrew from responding to the tender over roller coaster disputes about protection of intellectual property and guaranteed rates. For its part, after a long-tangled process, Turkey agreed to guarantee rates to the Russian plant.

Rosatom was the sole bidder on the Akkuyu project after three western consortiums withdrew from responding to the tender over roller coaster disputes about protection of intellectual property and guaranteed rates. For its part, after a long-tangled process, Turkey agreed to guarantee rates to the Russian plant.

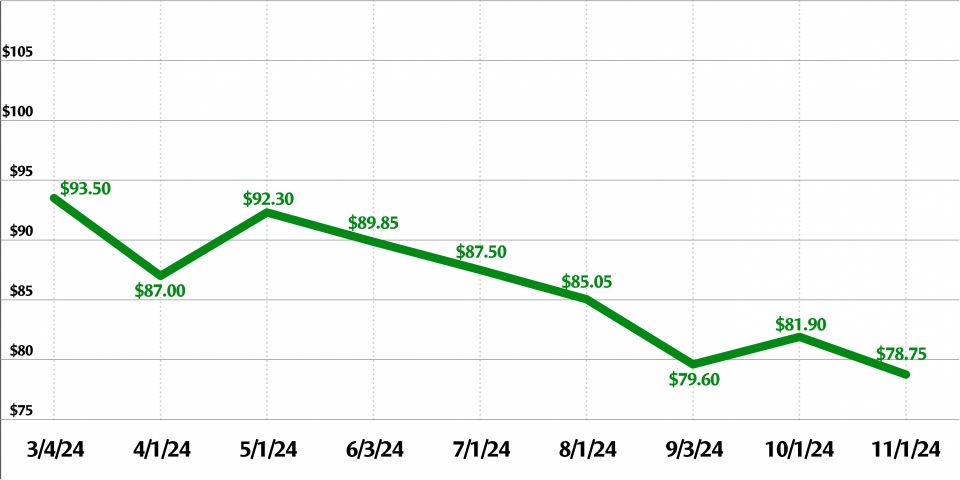

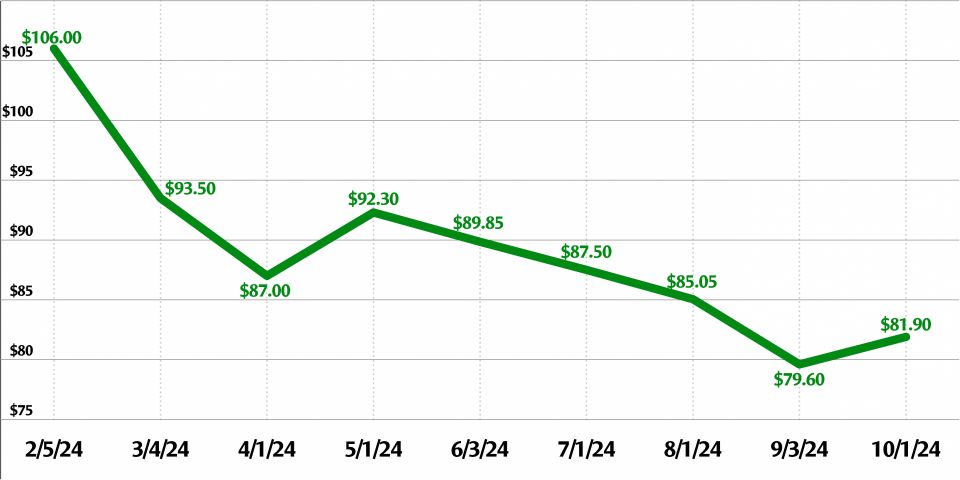

Now the Russians want to build the second and third nuclear power stations, but they have competition. There is another reason why Rosatom is not a slam dunk for the second and third power stations. The price has gone up on the first one.

On July 12, Interfax, a Russian wire service, reported that Vladimir Ivanovskiy, Russia's ambassador to Ankara, said that the Akkuyu nuclear power plant might cost Turkey more than planned.

"Inititally its cost was estimated at $20 billion, but I think it will be much more-about $25 billion," he told Russian journalists in Moscow. That's not going to make the Turkish government willing to give the Russians an unconditional green light for either of the next two projects.

South Korea pulls out of Sinop

South Korea, which inked a $20-billion contract with the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in December 2009 to build four 1,400-MW reactors, is still interested in doing business with Turkey. Despite two rounds of negotiations, however, the two side still hadn't come close to signing a contract, as in late 2010, South Korea and Turkey were at loggerheads over whether the Turkish government would guarantee financing from South Korea.

The South Korean government, which is already deeply committed to the UAE deal, may have looked at its books and decided it didn't have the ability to do another project of that size. Since then, South Korea has been exploring international financing without much success.

Playing the China card

China also has shown interest in the Turkish deal, and clearly has the money to pay to play. China, however, does not have a reactor design of its own to offer for export and no experience in financing reactor deals in global markets.

These drawbacks didn't stop Turkey's Deputy Prime Minister Ali Babacan from leading a trade mission to China in February 2012 to talk nuts and bolts about a nuclear energy deal.

Babacan reportedly told the Chinese that the second nuclear power station at Sinop on the southern Black Sea coast was pretty much a toss-up between Russia and Japan. He added, however, that the third site, near Turkey's border with Bulgaria, was fair game. China has not asked for financial guarantees for a nuclear power station, which has been a sticking point with South Korea.

By the time Turkey is ready to build that plant, probably around 2015, China is expected to have its own 1,400-MW version of the Westinghouse AP1000 ready for export. China's state-owned nuclear power firms-China National Nuclear Corporation and China Guangdong Nuclear Power Corporation-have growing ambitions to play in the global nuclear export markets especially for nations like Turkey.

The February 2012 trade mission was followed by an official state visit to Beijing in April by Turkey's prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan. He signed a memorandum of understanding for cooperation on nuclear energy with his Chinese counterpart, Wen Jiabao.

In a change from the February meeting, Erdogan noted that plans for Turkey's second power station, originally slated to be built by Japan or South Korea, were in flux.

Japan tries to re-enter the market

Japan originally proposed a team composed of Toshiba and the Tokyo Electric Power Company. With the collapse of TEPCO's finances due to the Fukushima crisis, however, that consortium pulled out of the Turkey venture.

In October 2011, Mitsubishi said that it would explore bidding on the contract for the Synop project in cooperation with Japanese utility Kansai Electric Power Company. Construction would be handled by GDF Suez, a French multinational construction company. Japan's government has also supported Hitachi's plans to build nuclear reactors in Vietnam. It isn't clear, however, whether or not Japan has put forward a solid proposal to Turkey.

Can Canada succeed with Candu?

Meanwhile, SNC Lavalin, a Canada-based company and owner of the reactor division of Atomic Energy of Canada Limited, approached Turkey in April 2012 with a proposal to build 3 Gwe, the equivalent of four Candu-6 pressurized heavy-water reactors, at Sinop. At an energy conference held in Istanbul, Turkey's energy minister Taner Yildiz said that SNC-Lavalin had six months to prepare a feasibility study as part of its proposal.

What's interesting about this deal is that SNC Lavalin vice president Ala Alizadeh told the Anatolia News Agency, a Turkish wire service, on April 20 that financing would be provided by Chinese investors, which means state-owned nuclear firms.

The future is still unknown

Turkey has a history of mercurial negotiations with reactor vendors. It doesn't have the capital to finance the units, which is why the Russian and Chinese offers look promising right now.

Russia's cost increase at Akkuyu, however, and the lack of a market-ready reactor for export from China, complicate what appears to be a choice of one or the other that could be made solely on available capital.

Japan's bid seems like a long shot because it isn't offering financing as part of its proposal.

An option by a Chinese state-owned nuclear organization to finance Candu-6 reactors could be the wild card in the Turkey nuclear market.

_____________________

Dan Yurman publishes Idaho Samizdat, a blog about nuclear energy and is a frequent contributor to ANS Nuclear Cafe.