Upon hearing this news, it was hard not to feel a slight sense of guilt that we, as a cancer research community, have not yet eradicated this horrible disease. In the year 2011 alone, breast cancer impacted the lives of an estimated 230,480 women in the United States. It is also difficult to not feel frustrated with the limited amount of money that our nation spends on cancer research, and even more so by the fact that this budget is stagnant and constantly threatened.

The National Cancer Institute (NCI), our country's preeminent funding agency for cancer research, has an annual budget of about $5 billion. When compared to, for example, the $12 billion spent by the United States every month in 2008 on Middle East conflicts, NCI's budget and the war on cancer seems like an extremely small fish in a very big pond. Cancer research will continue to be held hostage at this year's congressional budget meeting, while patients and their families hold on to their hope for a cure.

I too share this hope. Along with increased awareness programs, such as Breast Cancer Awareness Month, new scientific achievements in screening and therapy are improving survival rates amongst breast cancer patients and are paving the way for a cure to this disease. This improvement is largely due to advances in the ability to harness the beneficial power of ionizing radiation to detect and treat breast cancer.

Lesions smaller than a millimeter can now be detected with mammography. A mammography unit fires a beam of x-rays through the breast, taking a snapshot of the tissue under the skin. Because cancerous tissue is often denser than normal breast tissue, it casts a shadow, making it visible to the naked eye on a monitor screen. Currently, the American Cancer Society recommends yearly mammograms at the age of 40 and higher, whereas a clinical breast exam every three years is recommended for women in their 20s and 30s. While it is common for women to be concerned about the risks associated with screening, mammograms actually result in a very low dose (approximately 1.5 mSv to the glandular tissue), which correlates to a minute risk. Certainly the gain from undergoing screening greatly outweighs the risk, as early detection is key to successful treatment outcomes.

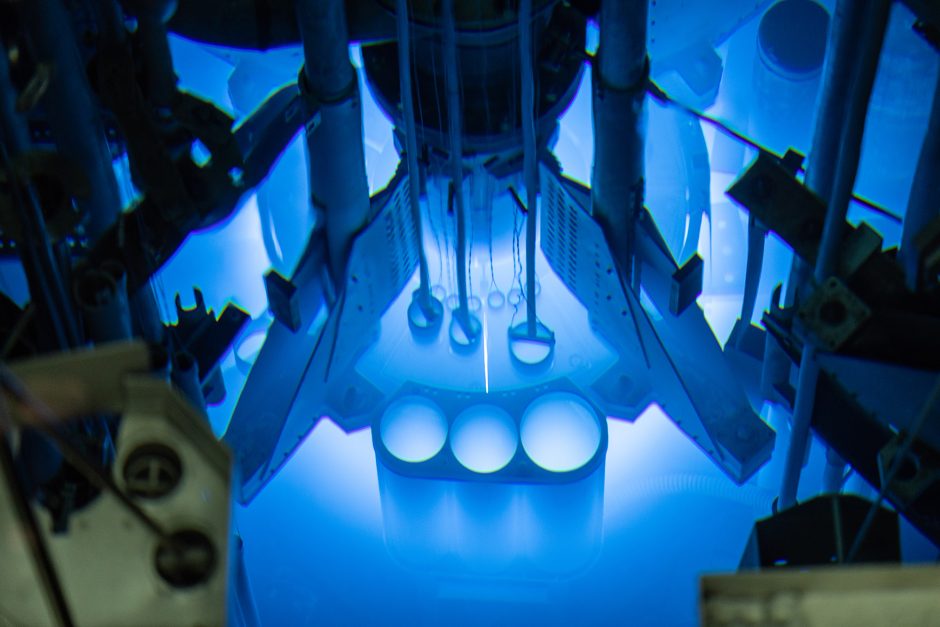

We are also making tremendous strides in our ability to treat breast cancers with radiation. Many patients each year are treated with radiation produced by a medical linear accelerator. A medical linear accelerator is a sophisticated machine that generates high-energy x-rays or electrons that are directed at cancerous tissue. Using metal blocks placed within the accelerator, the treatment beam can be focused directly at the cancerous region in the breast, while healthy tissue can be spared from being irradiated.

We are also making tremendous strides in our ability to treat breast cancers with radiation. Many patients each year are treated with radiation produced by a medical linear accelerator. A medical linear accelerator is a sophisticated machine that generates high-energy x-rays or electrons that are directed at cancerous tissue. Using metal blocks placed within the accelerator, the treatment beam can be focused directly at the cancerous region in the breast, while healthy tissue can be spared from being irradiated.

Alternatively, radioactive sources (e.g. Iridium-192) and miniature accelerators the size of the core of a pencil can now be implanted adjacent to tumors to provide even better treatment precision. Even more exciting are therapy interventions that combine ionizing radiation with novel pharmaceuticals to take advantage of the benefits offered by each. Likely, it will be these therapy "cocktails" that will result in a breast cancer cure.

With the help of radiation in medicine, tremendous advances have been made in the detection and treatment of breast cancer, and I remain optimistic that we are on the verge of scientific breakthroughs that will save the lives of thousands of more women each year.

______________________________

Bryan Bednarz is assistant professor of medical physics at the University of Wisconsin. His research focuses on solving problems that involve the interface between physics and biology. He received a B.S. and M.S. degree from the Department of Nuclear Engineering and Radiological Science from the University of Michigan, followed by a Ph.D. from the Department of Nuclear Engineering and Engineering Physics at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. He has been an active member of ANS since 2001 and serves on the Executive Committee of the ANS Biology and Medicine Division.

Bryan Bednarz is assistant professor of medical physics at the University of Wisconsin. His research focuses on solving problems that involve the interface between physics and biology. He received a B.S. and M.S. degree from the Department of Nuclear Engineering and Radiological Science from the University of Michigan, followed by a Ph.D. from the Department of Nuclear Engineering and Engineering Physics at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. He has been an active member of ANS since 2001 and serves on the Executive Committee of the ANS Biology and Medicine Division.

As a cancer researcher, I am constantly reminded of the horrific impact that breast cancer has on women and their families. This past week I received notification from my boss informing me and others that a work colleague's daughter had recently passed away from breast cancer at the age of 40-certainly this reminder was much closer to home than usual. It is difficult to imagine the pain and suffering my colleague and his wife are now experiencing, adding to what I am sure was a nerve-racking and exhausting period of consultations for the family and treatments for his daughter.

As a cancer researcher, I am constantly reminded of the horrific impact that breast cancer has on women and their families. This past week I received notification from my boss informing me and others that a work colleague's daughter had recently passed away from breast cancer at the age of 40-certainly this reminder was much closer to home than usual. It is difficult to imagine the pain and suffering my colleague and his wife are now experiencing, adding to what I am sure was a nerve-racking and exhausting period of consultations for the family and treatments for his daughter.