Pioneering STURGIS will go to shipbreakers

Nuclear barge STURGIS; photo from US Army Corps of Engineers

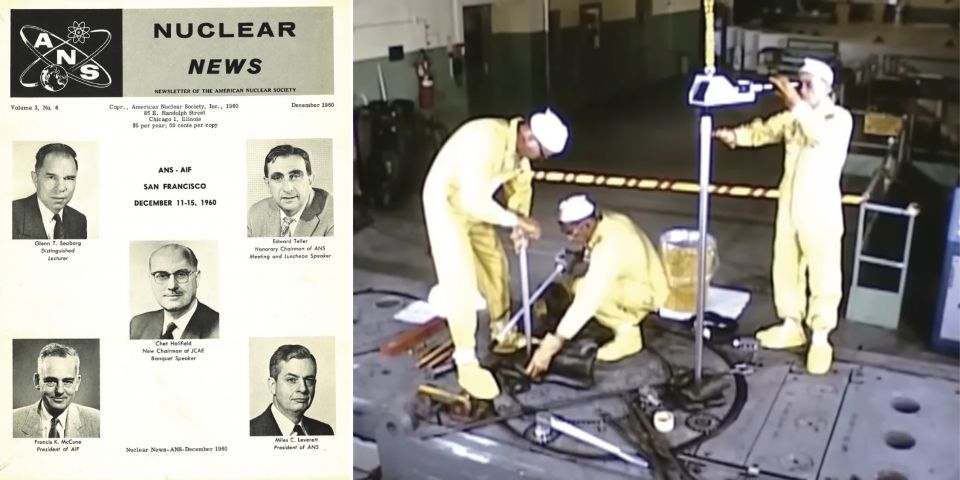

Last week, we were reminded of a mostly forgotten but ambitious effort spanning the late 1950's and 1960's by the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) and the U.S. Army-to develop a versatile range of small nuclear power plants-when it was announced that CB&I had been awarded a contract to decommission the former Army nuclear power plant barge STURGIS. While many have recently touted the Russian Akademik Lomonosov as the "first floating nuclear power plant," the expected completion date for that plant in 2016 will put it almost exactly a half century later than the successful STURGIS.

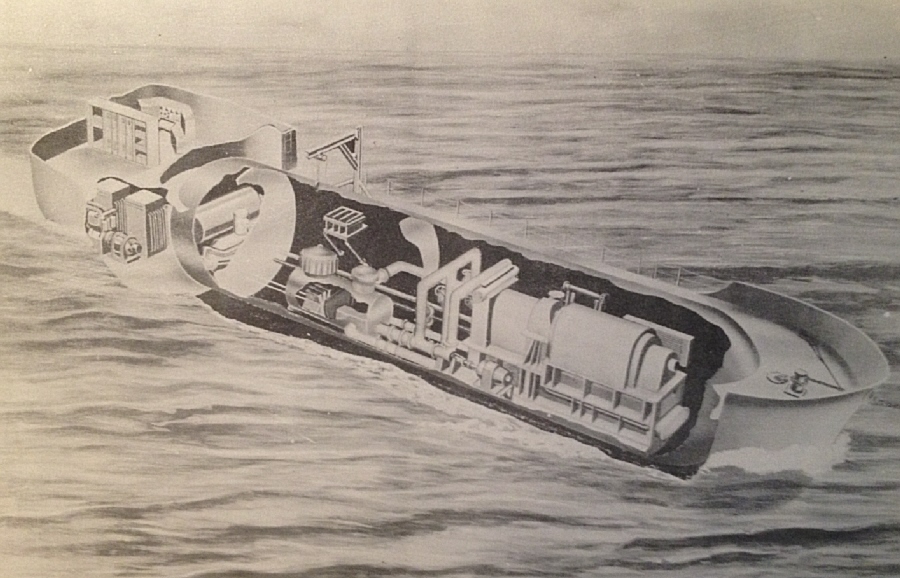

The first glimpse of the concept for this floating power station came in the late 1950's as the Army and the AEC worked to develop a wide range of small power plants (the Army's range of nuclear plants was given an upper bound of 40 MWe) for stationary, portable or mobile applications.

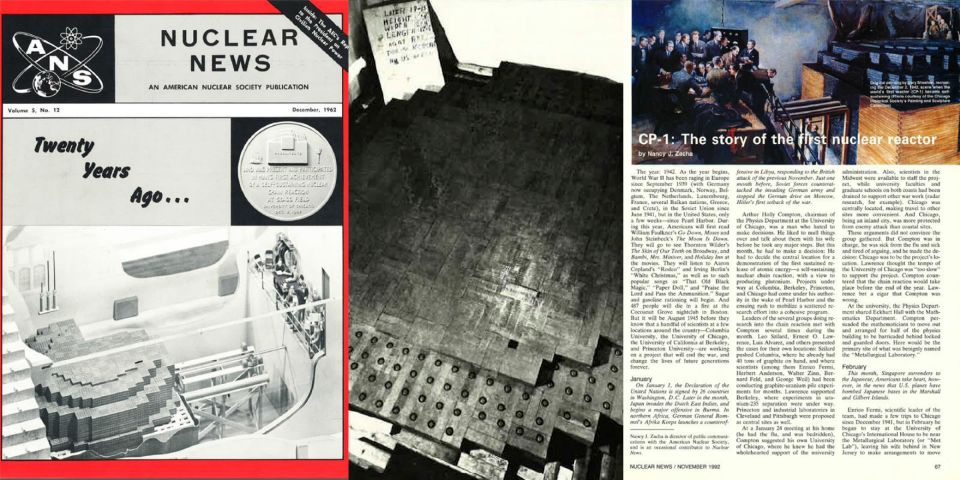

The earliest concept for what became the STURGIS in an illustration from the book "Army Nuclear Power Program," published by the Engineer School, Fort Belvoir, 1958. Under "Possible Future Projects" is "Barge-mounted Plants," described thus: "Another type of mobile plant which has been considered, would be mounted on a barge as shown in Figure 7 or on a mobile pier. Such plants could be built to furnish large blocks of electric power for remote installations and for emergency use both overseas and in the United States." (Will Davis collection)

Eventually it was decided to convert an existing ship. The Martin Company, a subsidiary of the Martin-Marietta Corporation, was selected to build the 10 MWe pressurized water reactor plant for this project. Martin had already been awarded the contracts for the small PWR plants used at Sundance Air Force Station, Wyoming (1.0 MWe and 2.0 MWt space heating) and at McMurdo Sound, Antarctica (1.5 MWe.)

Although STURGIS is often said to have been converted from a Liberty Ship (which originally was supposed to have been the SS Walter F. Perry, but ended up being the SS Charles)-in fact it was over one-third new; a brand new, and wider, midsection was inserted between the bow and stern of the Second World War vessel.

Erhard Koehler, an acknowledged expert on the nuclear powered merchant ship N.S. Savannah, and familiar with the STURGIS, elaborates on the construction of the new configuration. "The midbody, which contains the nuclear plant, turbogenerators, control room, and superstructure were all newly built. So although the STURGIS is often said to have been 'converted from a Liberty Ship,' that really isn't quite true. It may have been a necessary administrative fiction at the time." The new section also contained heavy concrete radiation shielding and collision protection for the power plant.

The powerplant was small, but conventional; it contained a 45 MWt pressurized water reactor which itself had a two-region core, and interestingly (for nuclear engineers, anyway) had boron poison added to its fuel cladding. The core was designed to run one year before a fuel shuffle / reload (in which the 16 inner elements would be removed, the 16 outer elements moved to the inner positions, and 16 new elements added in the outer positions). The plant had a single loop and a vertical steam generator, with two reactor coolant pumps.

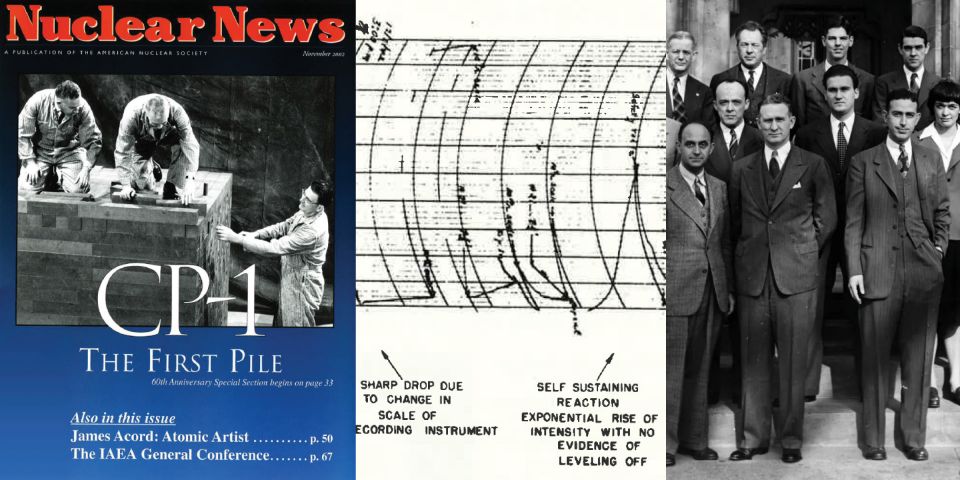

The complicated construction process for the ship was begun in 1963 when the Cugle was pulled from the Maritime Administration's reserve fleet; it ended with testing of the completed plant at the Army's station at Fort Belvoir, Virginia (where its original SM-1 nuclear plant was constructed and where a large amount of training was also performed.)

STURGIS testing at Fort Belvoir. US Army Corps of Engineers.

The STURGIS tested at Fort Belvoir for approximately one year, after which it was moved to the area of the Panama Canal, where it was more or less semi-permanently stationed at Gatun Lake for the purpose of delivering reliable, around the clock power to this vital resource. Eventually the Panama Canal Company installed extra (non-nuclear) generating assets, rendering the STURGIS' services unnecessary; in addition, the Army was getting out of nuclear power. The plant was shut down for the last time in 1976, and the ship eventually made its way to the James River Reserve Fleet. Koehler notes that after about 15 years, the languishing STURGIS was joined by the N.S. Savannah, which was tied to it. STURGIS was occasionally moved to drydock as required for maintenance and upkeep-according to Koehler, most recently in late 2007 - early 2008.

"There are a couple interesting ties between STURGIS and SAVANNAH, not the least being the 12 years that they were literally tied to one another in the reserve fleet," says Koehler, who also relates a little known and more serious relation the two have. "When B&W (the reactor vendor for the SAVANNAH) declined to bid for the STURGIS contract, one of their lead engineers from the NSS project, Zelvin Levine, left B&W and went to the Martin Company. Martin won the contract, and Zel was a senior project manager for the conversion." It's interesting to note that when Oak Ridge National Laboratory was performing supportive analytical study of the nuclear characteristics of the core for the STURGIS' power plant (officially designated as the MH-1A plant) its characteristics were similar enough to those of the reactor on SAVANNAH that much of the work was carried over. However, it's important to point out here that the two aren't identical.

Erhard also notes that the N.S. Savannah Association, Inc. recently received from Zel Levine some papers "that include several preliminary and final volumes from the STURGIS Safeguards Report," which means that some of the ship's documentation at least will survive.

Will any of the vessel itself survive? Probably not much. Koehler tells ANS, "The two steaming Liberty Ship museums (Jeremiah O'Brien in San Francisco and John W. Brown in Baltimore) have been given opportunities from the Army to salvage useful equipment from STURGIS during the project. The Army Corps has a number of curatorial artifacts already removed and preserved. They are in the process of consulting under the National Historic Preservation Act to determine any further mitigation actions that will be taken prior to the dismantlement. However, at the moment it doesn't appear that any other features of the ship are slated for preservation. As an example, two nearly identical control rooms are already preserved; one at Fort Belvoir, so the STURGIS console may not be removed."

STURGIS photographed by Erhard Koehler on April 10, 2014.

Eventually, later this year, the STURGIS will make its way to Galveston, Texas, where the decommissioning of the power plant section will take place. The ship's power plant will be dismantled and disposed of in the same manner as commercial nuclear plants, with waste being shipped to approved disposal sites (which have not yet been determined). Once this section has been removed the rest of the ship will be scrapped at Brownsville, Texas. The Army Corps of Engineers estimates presently that the entire process "should take less than four years," according to its announcement. (There will be a public meeting in Galveston this summer to "provide more details and answer questions.") With the dismantling of the STURGIS, another vestige of a once-promising but now ever-vanishing program disappears, although as we've seen with the recent frenzy over the Russian floating plant, the concept is as sound today as it was a half century ago.

For more information:

Final Environmental Assessment - Decommissioning and Dismantling of STURGIS and MH-1A

Decommissioning and Dismantling of STURGIS - US Army Corps of Engineers. This page has links to videos of the construction and testing of STURGIS.

Will Davis posted on the STURGIS on March 31 at Atomic Power Review.

World Nuclear News posted on the STURGIS on April 14.

CB&I Press Release on Contract Award for STURGIS decommissioning.

A view abeam of the STURGIS. Photo by Erhard Koehler, April 9, 2014.

Will Davis is the communications director for the N/S Savannah Association, Inc. where he also serves as historian and as a member of the board of directors. He is also a consultant to, and writer for, the American Nuclear Society; an active ANS member, he is serving on the ANS Communications Committee 2013-2016. In addition, he is a contributing author for Fuel Cycle Week, is secretary of the board of directors of PopAtomic Studios, and writes his own popular blog Atomic Power Review. Davis is a former US Navy reactor operator, qualified on S8G and S5W plants.

Will Davis is the communications director for the N/S Savannah Association, Inc. where he also serves as historian and as a member of the board of directors. He is also a consultant to, and writer for, the American Nuclear Society; an active ANS member, he is serving on the ANS Communications Committee 2013-2016. In addition, he is a contributing author for Fuel Cycle Week, is secretary of the board of directors of PopAtomic Studios, and writes his own popular blog Atomic Power Review. Davis is a former US Navy reactor operator, qualified on S8G and S5W plants.