In an Era of "Firsts," an "Almost"

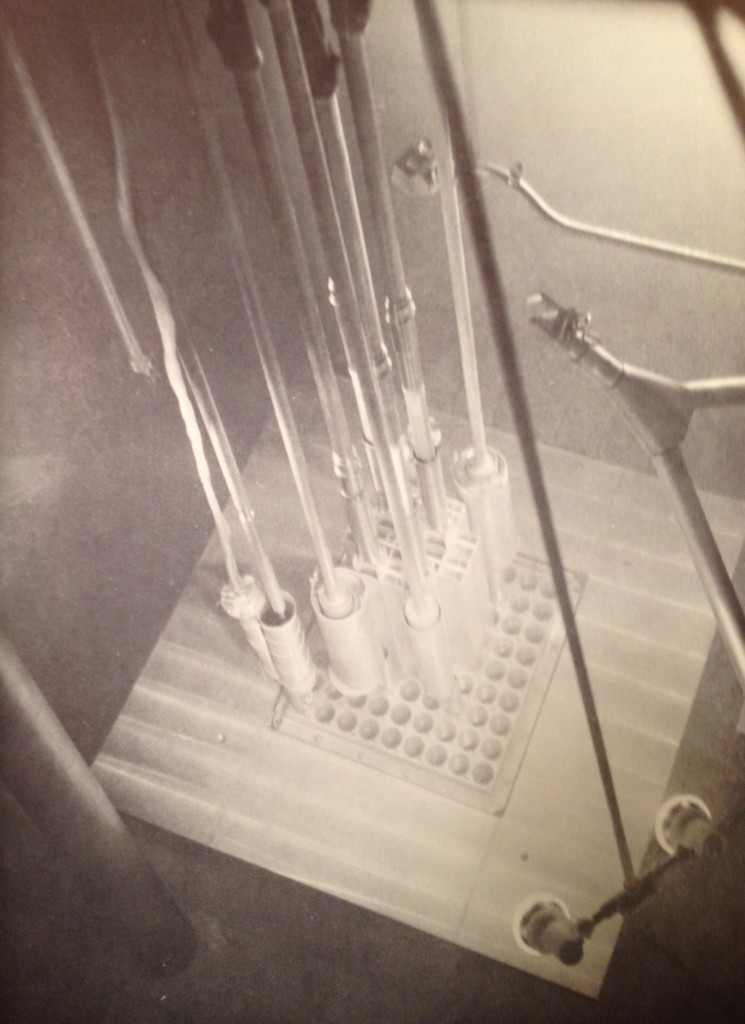

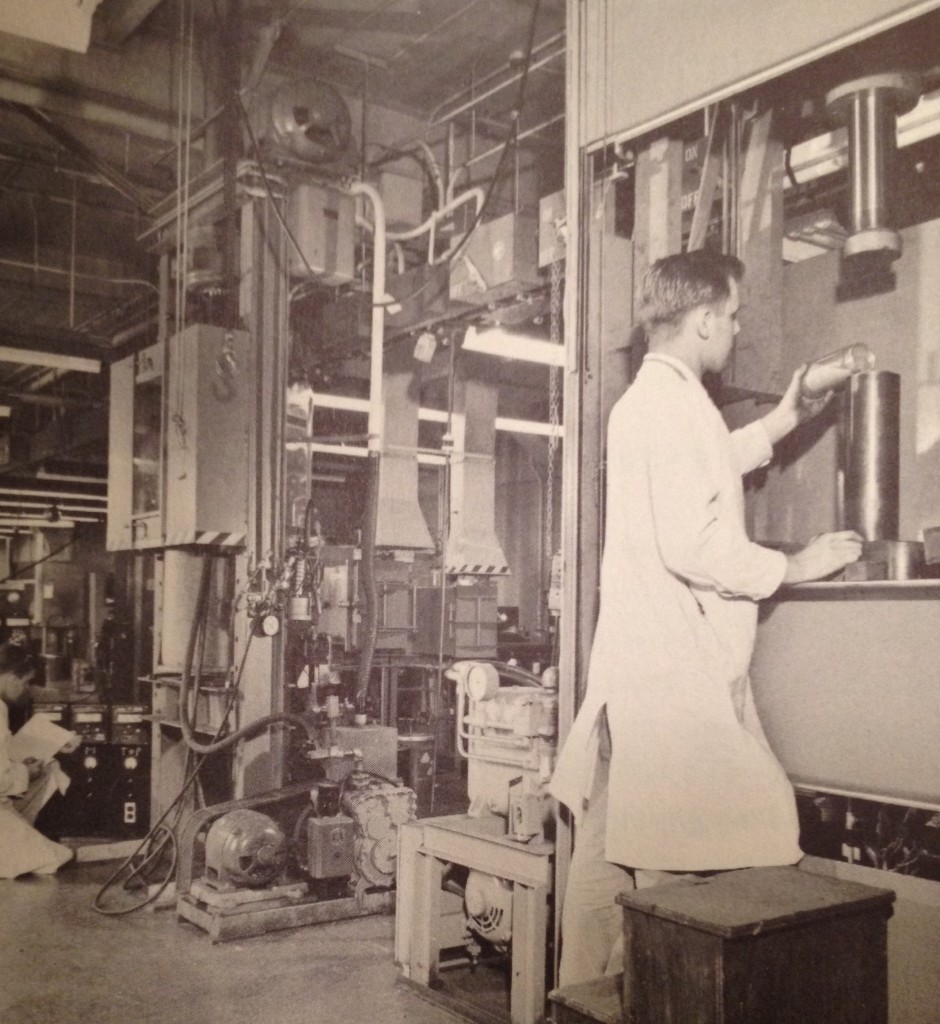

Powder Metallurgy Facility, Sylvania-Corning Nuclear Corporation, Bayside, N.Y. From Will Davis' collection.

The era of the "first nuclear build" in the United States (from the Manhattan Project of the Second World War at the earliest, through the final commercial plant orders in 1978) was by nature one of nearly continuous "firsts" in its opening decades, as nuclear energy moved from being a thought to a possibility to a reality and took on many forms and nuances.

Among the many "firsts" was the formation in April 1957 of what was said to be at that time the "World's First Nuclear Fuel Company," when Sylvania Electric Products Inc. and Corning Glass Works combined their efforts in nuclear technology to form Sylvania-Corning Nuclear Corporation (SYLCOR). The company had as its main facilities a well-equipped research laboratory at Bayside, N.Y. and a nuclear fuel manufacturing plant located at Hicksville, N.Y.

SYLCOR Commercial Nuclear Fuel Production Plant, Hicksville, New York. Will Davis collection.

Of course, other companies had made nuclear fuels prior to the formation of SYLCOR; the formation of SYLCOR instead marked the launch of the first privately held company whose entire field was the development and production of nuclear fuel while itself not being a reactor vendor.

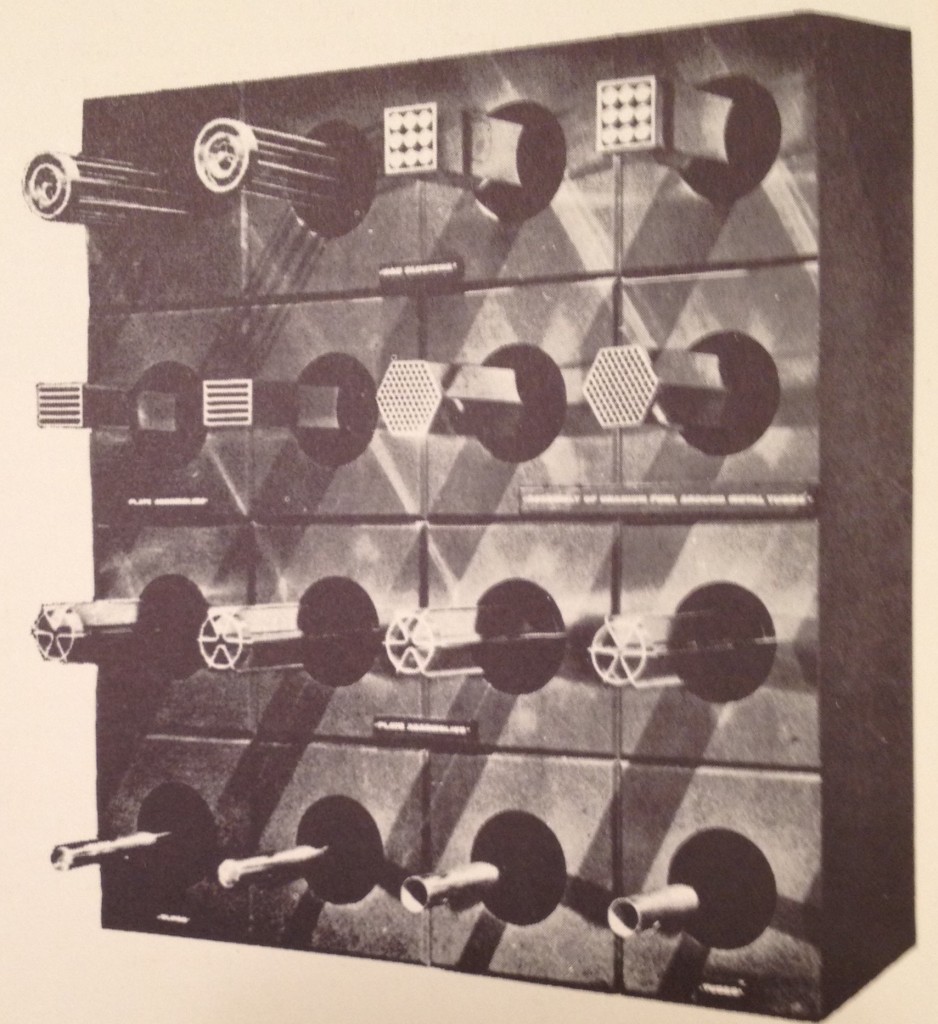

SYLCOR quickly made something of a name for itself providing highly enriched plate type fuels, for some very well known early reactors which included the Materials Testing Reactor at NRTS; several reactors at the Brookhaven National Laboratory; the Chalk River Pool Test Reactor; the Massachusetts Institute of Technology reactor; the APPR or Army Package Power Reactor; and the Netherlands Test Reactor as just some examples. The company also fabricated other types of fuel, such as hollow slug type for the Savannah River Production Reactors, pin type fuel for the Enrico Fermi Atomic Power Plant, and pellet type for the Pathfinder Atomic Power Plant.

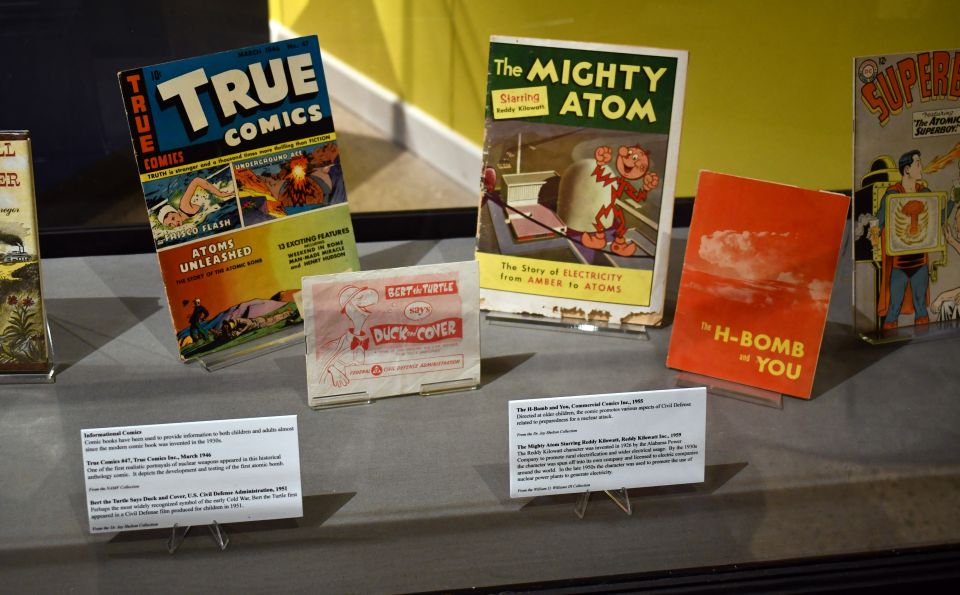

Soon the company was not only fabricating all sorts of fuel and moderator materials but actually offering to the trade four completely standardized, "off the shelf" models of fuel elements. The A-1091-C and A-1091-F types each had ten aluminum fuel plates per fuel element, enriched to 90 percent; the elements were either curved plate or flat plate as denoted by the suffix letter. Similarly, the A-1891-C and A-1891-F standard fuel elements had 18 fuel plates per element, also 90% enriched, and either curved or flat plate as denoted. These elements could be (and were) ordered from SYLCOR's catalog for the construction of test and research reactors; SYLCOR even developed a standardized book of Terms of Sale and Conditions to speed transactions.

Display of various types of fuel elements manufactured by SYLCOR. From brochure in Will Davis collection.

SYLCOR experienced a number of mis-steps and made a number of business miscalculations as it tried very hard to compete with the very large and well funded fuel production efforts of the reactor vendors. Perhaps the most surprising of its failed efforts was one undertaken in 1959 wherein the company would have taken complete control of the back end of the fuel cycle for commercial reactor owners.

A proposal book in this author's collection, which carries a date of September 1959 outlines a proposal by SYLCOR to Consolidated Edison wherein the transportation and reprocessing of the spent fuel from the Indian Point commercial nuclear power plant would have been contracted to SYLCOR. In this venture, SYLCOR had joined forces with Knapp Mills who SYLCOR described in the proposal as "the world's leading cask designers and builders." This company would assist SYLCOR with the physical equipment necessary to transport the spent fuel from Indian Point to the Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

The proposal contained two options. "Plan A" was for SYLCOR to provide for Con-Ed "a complete cask and spent fuel transportation service" to Oak Ridge; in this arrangement, Con-Ed would retain "prime responsibility" for the spent fuel while in transit and would have to make arrangements with the AEC for the reprocessing of the spent fuel.

Far more ambitious was "Plan B," in which SYLCOR would actually have purchased the spent fuel (or, taken control of the AEC license for it) for a fixed lump sum contract price. SYLCOR would then have assumed total responsibility ("within existing laws and regulations") for the spent fuel from the placement of the fuel in the Knapp Mills supplied casks at the plant through to getting the fuel to Oak Ridge. The fuel would have been reprocessed "to SYLCOR's account," meaning that materials from the reprocessing would then have been available for SYLCOR to use. The significance of the second proposal is made clear in the following statement carried in the proposal:

"Under Plan B it will not be necessary for Con Edison to conduct any activities in the spent fuel handling or reprocessing phases of the nuclear fuel cycle once the spent fuel has been transferred to SYLCOR's responsibility at the Indian Point site."

The proposal goes on to say that the development of Plan B, preferable to both parties, was only made possible "during the last few weeks" as a result of the amendment of the Atomic Energy Act of 1954 to allow licensees (SYLCOR prospectively being one) to "enter into contracts with the AEC for reprocessing services."

SYLCOR would have been responsible under Plan B to develop all on-site procedures at Indian Point including those related to safety, exposure and criticality. It would have had to develop the handling equipment to get the spent fuel into the new transportation casks and provide it. SYLCOR would have been responsible to develop other procedures at the Oak Ridge end of the journey, and other equipment.

Under Plan B, SYLCOR would have paid Consolidated Edison $3,184,516.00 for five years worth of the spent fuel timed from the first spent fuel shipment.

History shows that while SYLCOR made at least two commercial proposals to essentially buy irradiated or used fuel (universally called "spent fuel" in those days) that no actual contracts were signed. The concept for taking the back end of the fuel cycle from the utilities was stillborn.

Although SYLCOR attempted other ventures in the nuclear fuel business, by 1960 part owner Corning Glass Works had had enough and in April 1960 Sylvania bought out Corning's interest; the company became the Sylvania SYLCOR Division. In June 1966 after failing to make headway against what was now a very competitive field with a number of commercial fuel manufacturers, Sylvania sold the entire subsidiary with all assets and licenses to National Lead Industries. The new owner immediately halted work at the former SYLCOR sites, marking the end of what had once been proudly proclaimed as "The World's First Nuclear Fuel Company."

(Author's note: The proposals are very complicated, and include far more detail than is suitable for the general reader. The author would be happy to discuss the details with those interested.)