Fort St. Vrain in Pictures: 6

The Fort St. Vrain Nuclear Generating Station completed and in operational service. Press photo in Will Davis collection.

The initial startup of the Fort St. Vrain station finally happened on January 31, 1974, which was roughly one month after the station had received an operating license from the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). As was the habit in those days with plants that were more experimental in nature than the light water plants, Public Service of Colorado had applied for and been granted by the AEC an operating license under Section 104(b) of the Atomic Energy Act. This provision, ostensibly for medical or for research and developmental reactors, allowed a great deal more operational flexibility to the operators and additionally required far less discussion with and approval by the AEC itself on various matters concerning plant design, operation, administration and developmental testing.

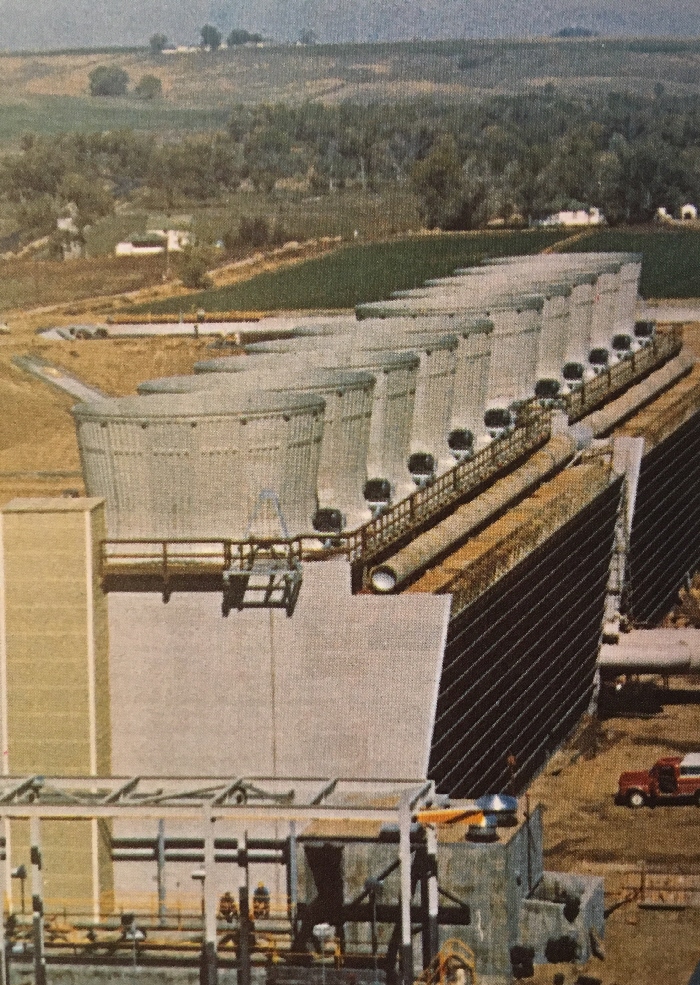

Cooling towers, Fort St. Vrain Nuclear Generating Station.

Because of the developmental nature of much of the design and construction of this very radically new plant design, it was not until 1979 that the owners were able to declare Fort St. Vrain to be in a status of "in commercial operation" - a sign that a plant is ready to provide continued, useful power to the grid and, hopefully, make money in the process.

As had happened during the run-up to commercial operation, nagging technical and operational problems continued to be experienced at the plant. Probably the most long-lasting was that of water getting from the helium circulator bearing system into the helium coolant circuit, which was described in one official report as "a generic problem at Fort St. Vrain." Moisture also entered the helium from the graphite, which was exposed to air and humidity during manufacture and refueling. This was considered a problem because of the degradation it would theoretically cause to graphite structures and, even, possibly the fuel particle coatings if not removed.

Worse in an immediate operational sense as a result of moisture being present in the system was the development of partial scram / failure to scram events at the plant at least twice; on one occasion, operators were unable to cause six rods to scram even after pulling rod drive fuses. Only after re-energizing the rod drives and inserting rods manually did the reactor have all rods on the bottom (even though it was shut down on the rods that did insert.)

Electric switchyard, Fort St. Vrain Nuclear Generating Station.

The moisture ingress events were primarily the result of the design of the helium circulators, which were shown in a previous installment. The use of both steam and water in the same machine which pumped the helium required helium and water seals, whose pressure balance could be upset a number of ways - leading to water being injected into the helium coolant system from the seals.

When a control rod stuck again on August 18, 1989, Fort St. Vrain was shut down to determine the cause. As always, plants take advantage of shutdown conditions to perform inspections if possible and during this shutdown a devastating discovery was made - namely, cracking of the main header pipe that routed steam from the 12 steam generator modules to the secondary plant. An assessment of the situation showed that replacing or repairing this large, ring shaped header would be prohibitively expensive for the plant, and the PSCo Board decided that it would permanently retire the plant on August 29, 1989.

Farming in sight of the Fort St. Vrain Nuclear Generating Station.

Fort St. Vrain lasted about ten years in service - longer by a couple years than the United States' first High Temperature Gas Cooled plant, Peach Bottom 1, which operated from 1967 through 1974. Fort St. Vrain had also outlasted something else - the stillborn "third round" of commercial HTGR plants. Several commercial HTGR plants based closely on Fort St. Vrain but with much higher output had been ordered by U.S. utilities from General Atomic in the early 1970's, but all of these were cancelled before being built (although at least one had an LWA or Limited Work Authorization.) Those plants were all cancelled because the estimated cost-to-construct skyrocketed during the contract negotiation period - the first of them being cancelled by the potential owners, and the last two being cancelled by General Atomic itself (leading to the claim that GA 'reneged' on the contracts in some quarters.)

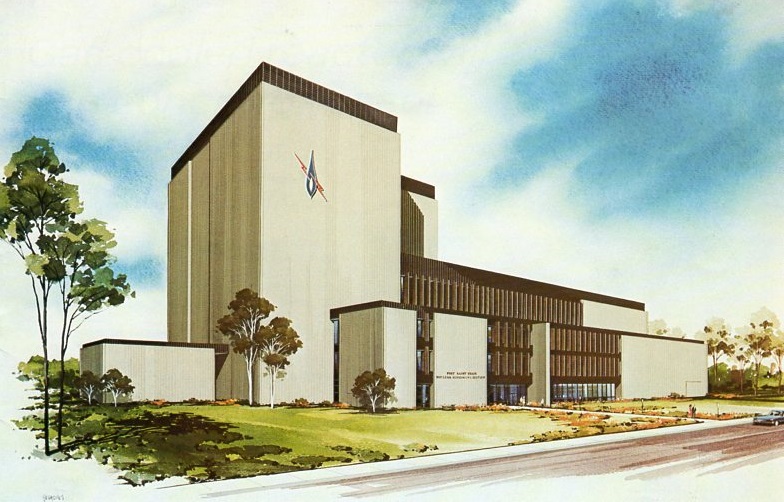

Fort St. Vrain Nuclear Generating Station.

The reactor's fuel elements were removed painstakingly over a long period lasting into 1991 and, very soon after, the nuclear decommissioning of the plant was begun as the owners had elected to immediately dismantle, rather than place the plant in SAFSTOR. All of the nuclear structure - that is to say, the graphite moderator blocks, the PCRV liner, upper and lower heads, etc. - was cut out and removed laboriously over a period lasting several years. Fort St. Vrain was finally released radiologically and had its license terminated by the NRC in August 1997. It should be noted that PSCo announced the decommissioning project was ahead of schedule and under budget when completed.

However, the plant does live on in a way. Early in the dismantling process, the owners began to think about repowering the plant and that's exactly what they did; gas turbine plants were added to the site, and these supplied steam in a combined-cycle arrangement to the original Fort St. Vrain turbine generator. Today, the plant operates as owner Xcel Energy's "largest gas fired plant in Colorado."

Fort St. Vrain Nuclear Generating Station is seen in the background; nearer us is the Visitor Center. Remarkably this visitor center still stands today.

Although Fort St. Vrain didn't last as long as many of its contemporary light-water cooled reactor plants, it did in many ways pave the way to development of later gas-cooled reactors by providing operational experience and proving out - or, in some cases, proving fallible - various design features that might be considered for future commercial gas-cooled reactor plants. Today, we're seeing greatly increased interest in high temperature reactors of all sorts, and gas cooled reactors are among those actively being considered as Small Modular Reactors or SMR's. Innovative features such as the prestressed concrete vessel and integral design, as well as the unitized fuel, might well carry forward to the next generation. If that's true, then the Fort St. Vrain experience will not have been wasted.

Will Davis is a member of the Board of Directors for the N/S Savannah Association, Inc. He is a consultant to the Global America Business Institute, a contributing author for Fuel Cycle Week, and he writes his own popular blog Atomic Power Review. Davis is also a consultant and writer for the American Nuclear Society, and serves on the ANS Communications Committee and the Book Publishing Committee. He is a former U.S. Navy reactor operator and served on SSBN-641, USS Simon Bolivar. His popular Twitter account is @atomicnews

Will Davis is a member of the Board of Directors for the N/S Savannah Association, Inc. He is a consultant to the Global America Business Institute, a contributing author for Fuel Cycle Week, and he writes his own popular blog Atomic Power Review. Davis is also a consultant and writer for the American Nuclear Society, and serves on the ANS Communications Committee and the Book Publishing Committee. He is a former U.S. Navy reactor operator and served on SSBN-641, USS Simon Bolivar. His popular Twitter account is @atomicnews