Clinch River in the Spotlight

.jpg)

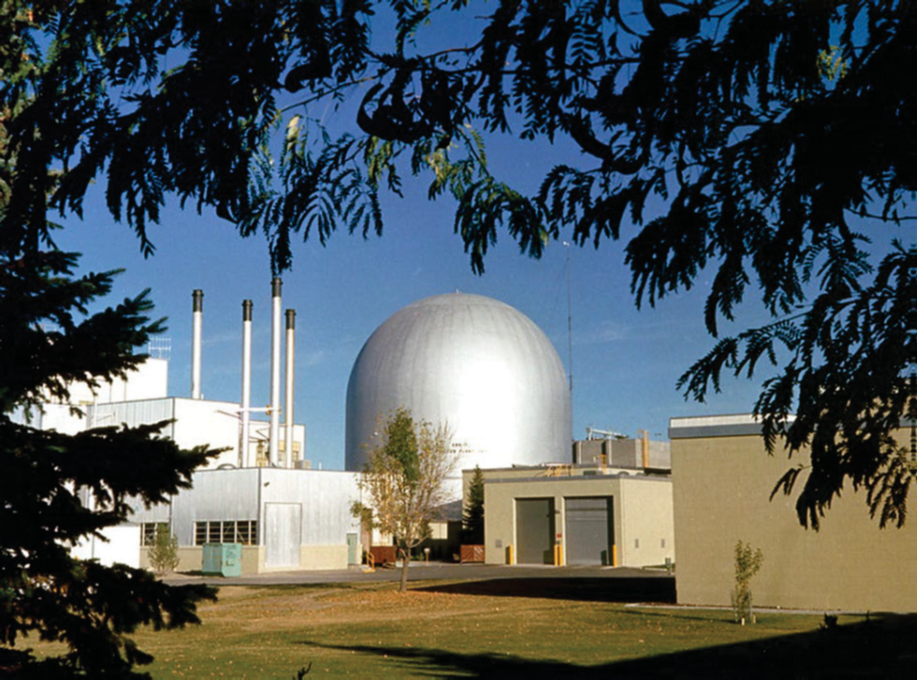

Last week’s announcement from the Tennessee Valley Authority about its “New Nuclear Program,” which outlines the potential development of the Clinch River site near Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Eastern Tennessee, is the catalyst for this week’s #ThrowbackThursday post. The Clinch River site was originally planned to be the location for the Clinch River Breeder Reactor, a project that, at the time, was meant to be the future of the nuclear industry in the United States.

The site was selected in the early 1970s to host the demonstration breeder reactor, but President Carter ended that soon upon becoming president in 1977. An article published last month looked at the May and June 1977 issues of Nuclear News, where it was reported that Carter had set his sights on the breeder reactor program.

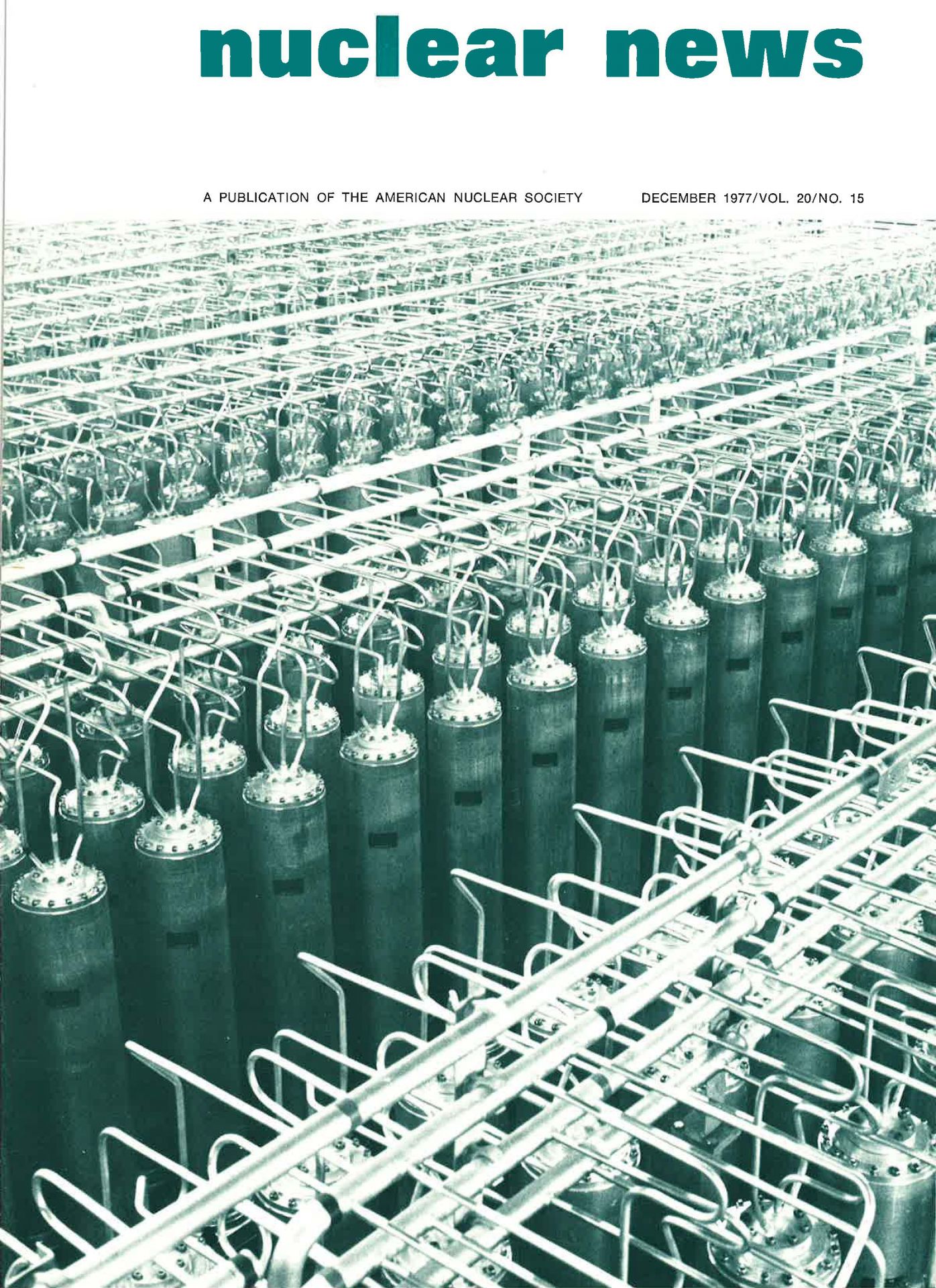

Cover of the December 1977 issue.

This week, Nuclear News is reviewing the December 1977 issue, which leads with the editorial by then editor in chief Jon Payne, titled “Clinch River: A significant symbol.” Payne stated, “As a symbol, the breeder, like nuclear technology in general, has increasingly fallen into disfavor, while alternative energies such as solar have become the favored symbols. Today's extravagant language about solar energy is reminiscent of the former optimism concerning nuclear energy.” That quote shows how supporters of nuclear are involved in the same arguments that the industry faced back in 1977. It’s taken only 45 years to get Clinch River back as a site for the potential future of nuclear.

Following Payne’s editorial is the Legislation section, which leads with the story “Carter vetoes CRBR, draws Congressional ire.” That column is posted below but can also be found on page 28 of the December 1977 issue of Nuclear News.

Carter vetoes CRBR, draws Congressional ire

President Carter moved again to strike down the Clinch River breeder reactor project as he vetoed the DOE Authorization Act of 1978, Civilian Applications. The Carter veto message, presented in its entirety on the opposite page, is centered on his objections to the breeder reactor and on the nonproliferation arguments he has presented on several occasions. The veto, in its timing and in the manner in which it was presented to the press, served to anger certain influential members of Congress who are most closely associated with this and other pieces of energy legislation now under consideration.

The sequence of events ran on this order:

November 4. Congress recessed with orders to return on November 29 to consider unfinished business, including the President's National Energy Plan, then in conference. Certain pro forma sessions were held in the interim, but it was stipulated that new legislation would be considered in the current session. Among the unfinished business: the supplemental appropriations bill, which includes $80 million for CRBR. This bill had cleared both houses and the conference before the recess and awaited final pro forma passage after Thanksgiving.

November 5. The DOE Authorization Act, which authorized $80 million for CRBR, had been on the President's desk for 10 days. If unsigned on the following day, it would pass directly into law. Early on the morning of November 5, the White House alerted the Washington press corps that a relevant statement on the Authorization Act would be made that day. Around noon, attempts were made by the White House staff to inform certain Congressional staff members—those associated with the committees that wrote the bill—that a veto message was imminent. Later in the day, Stuart Eizenstat, assistant to the President for domestic affairs, and his assistant, Katherine Schirmer, presented the President's text to the press. Almost everyone concerned with the bill heard about the veto on the radio or on TV.

As a background to this action, the Congressional leadership reportedly had asked the President not to veto the bill, seeing the action mainly as "symbolic" and warning that it would anger many members of Congress and would further jeopardize the National Energy Plan, then in deep trouble on Capitol Hill. Moreover, the leadership said, if the veto is sustained, the President must face the same issue again later this year with the supplemental appropriations bill, which he is not expected to veto. Informed sources say Speaker of the House Tip O'Neill (D., Mass.), told the White House something like this: "If the President signs the appropriations bill, and then sends up a recission order on the CRBR funding, Congress can beat him on this one with a simple majority, and we're back to square one."

The response: As expected, the veto evoked an immediate response from across the country, and especially from those members of Congress who were responsible for getting the authorization bill passed (see "Window on Washington," p. 31). Rep. Mike McCormack (D., Wash.), who is among the most influential nuclear advocates on Capitol Hill, issued a public statement (see p. 30) that focused attention on the impact the veto has on the entire national energy program.

Among the other pertinent comments, the following summaries are indicative of how much tempers have been aroused over this issue: Rep. Olin Teague (D., Texas), chairman of the House Committee on Science and Technology, called the veto a "rash, irresponsible act," and said it is a direct denial of the President's claim that the energy crisis is "the moral equivalent of war." Carter has revealed, Teague said, that he does not know "either his enemies or his allies in that war." Summarizing the months of "strenuous, conscientious effort" his committee and others had put into weighing the evidence and producing the bill, Teague said they had arrived at a compromise that should have been acceptable to the President, because the bill did not approve actual construction of CRBR until an effective nonproliferation program could be worked out.

Teague said that a large majority in Congress is now convinced that "breeder technology is an imperative need," but, he added, this is an energy matter. Because of this, he said he had "great concern" because no one from DOE participated in the veto announcement. Naming the two White House staff members who made the press presentation, Teague said this of Schirmer: "I am told [she] is a crusading environmentalist." And he added: "This raises a troublesome question as to who it is that really has the President's ear in these matters. Where were his energy and science experts?"

Sen. Frank Church (D., Idaho), chairman of the authorizations oversight subcommittee of the Senate Committee on Energy and National Resources, said this: "On this issue, I think Congress is right and the President wrong. By refusing to build the breeder reactor, while other nations proceed to do so, we not only retreat from reality, but we are bound to lose our leadership role in shaping the global control system which the use of plutonium fuel demands."

TVA board chairman Aubrey Wagner said: "Mr. Carter went against the judgment of 90 percent of the scientists in this country. It is things like this that can make us a second-rate power before we know it." Also: "We'll probably end up buying breeders from the French, and I don't know if there's much difference between imported electricity and imported oil."

Industry spokesmen were much more cautious in their statements, with representatives from the American Nuclear Energy Council, the Edison Electric Institute, and the Atomic Industrial Forum saying only that they generally deplored the President's action.

The veto message: The President said he based his objections to CRBR on three prongs—interference with nonproliferation goals, technical obsolescence, and unsound economics. The last two were the cornerstone arguments used by DOE Secretary James Schlesinger during Congressional hearings on the breeder. However, when a DOE official was asked why Schlesinger was not present when the veto message was made public, he replied that the whole issue is "overwhelmed" by nonproliferation concerns. Schlesinger did, however, favor the veto, he said.

All three points of contention were hotly debated during the prolonged Congressional hearings that preceded the drafting of the authorization legislation. Among his other reasons for vetoing the bill, the President cited limitations on storing spent fuel from foreign reactors. The limitation was thought to have been covered in the McClure amendment to the bill (after Sen. James McClure, R., Idaho), and it would give Congress a voice in determining the extent of the foreign-burned fuel storage program. McClure argued that our offer to store fuel burned abroad should not work to the detriment of the domestic fuel storage program.

The President also objected to the one-house veto over certain energy projects, including the criteria and commercial pricing structure to be worked out for government enrichment services, and to the stipulation that the administration must decide within six months what it is going to do with the Allied-General Nuclear Services reprocessing facility at Barnwell, S.C.

By vetoing the energy authorization package, Carter has stopped dead all new energy programs that were expected to start up on October l, 1977, including those concerning electric vehicles, loan guarantees for synthetic fuels, automobile propulsion research, high-energy physics, and an international study on the use of the Barnwell plant. These cannot go forward without some kind of an authorization bill, and none is seen as forthcoming at any time in the near future. This is expected to be a rallying cry of the breeder advocates in Congress, who are saying that the President cannot be serious about the energy crisis if he strikes down all these vital programs.

Old, on-going energy projects, such as Clinch River, are now held in a kind of limbo, pending further authorizing actions.

The article went on to discuss options for Congress going forward to fund the Clinch River breeder reactor and noted that while Congress may be behind the project, “Carter was explicit on his intent to go the full distance on stopping CRBR funding.” While 1977 may have been a tough year for nuclear advocates, it seems now, 45 years later, that the future of nuclear power is bright with the possibilities of building small modular and advanced reactors at sites like Clinch River.