University of Tennessee hosts inaugural NEDHO Diversity Panel

The University of Tennessee–Knoxville Department of Nuclear Engineering hosted the inaugural Nuclear Engineering Department Heads Organization (NEDHO) Diversity Panel on October 27. The panel featured three African American speakers who discussed overcoming challenges in their engineering education and careers to find success. A common theme that emerged from the conversation was that, in addition to their own determination to succeed, all the panelists benefited from caring adult guidance during their youth, as well as from strong support from friends, family, and colleagues as they pursued their goals.

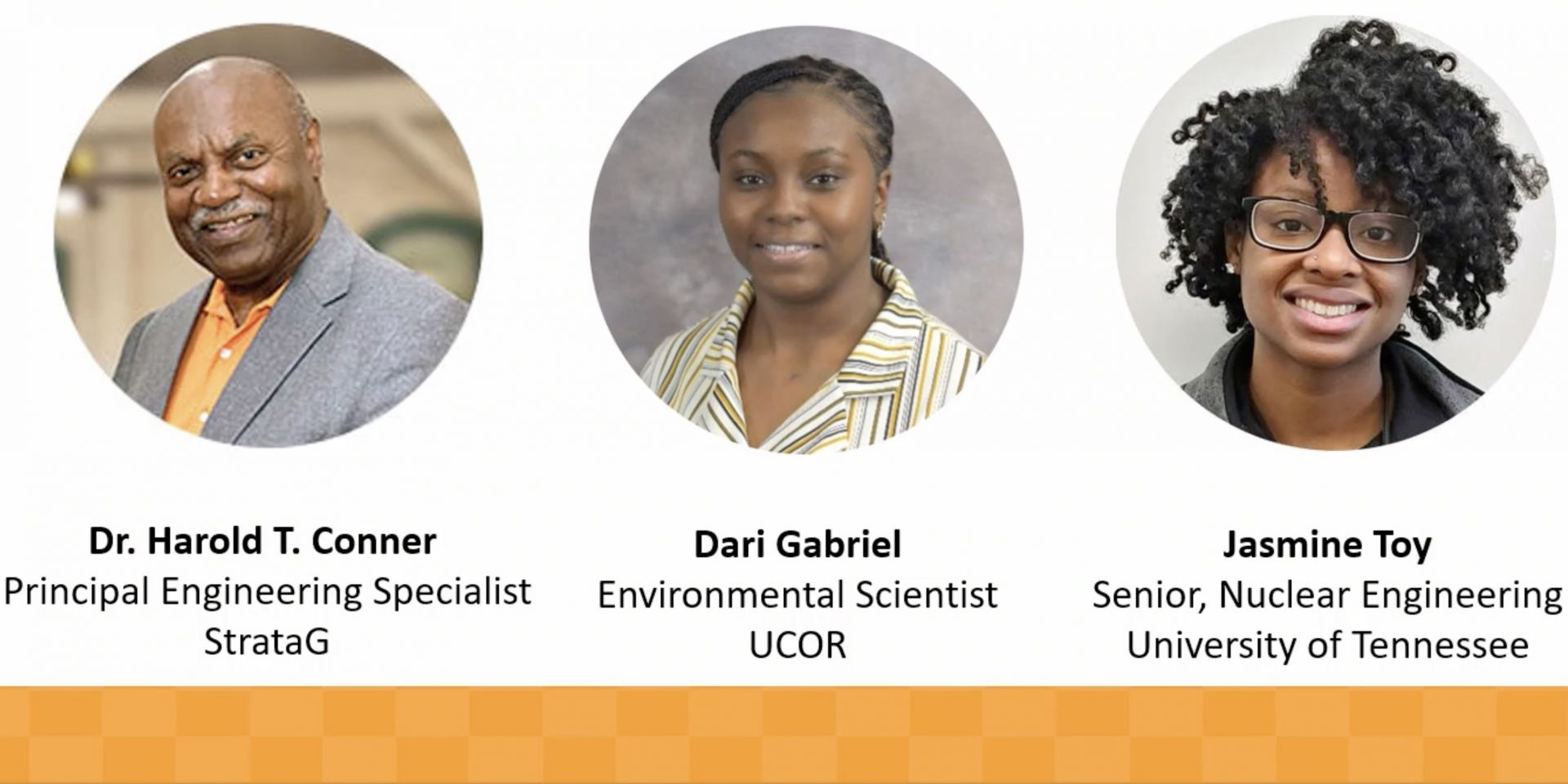

The Panelists: Invited to speak this year were Harold T. Conner, Dari Gabriel, and Jasmine Toy.

Conner has enjoyed a career of more than 55 years in nuclear energy. After being the first African American to earn a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering from the University of Tennessee, he went on to hold high-level positions at Department of Energy sites across the United States. Now “retired,” he serves as a consultant for United Cleanup Oak Ridge (UCOR), a contractor specializing in nuclear deactivation and decommissioning, and for Strata-G, an Oak Ridge company that supports DOE projects.

Gabriel, an environmental scientist with UCOR, manages waste reporting and other hazard-related compliance activities associated with the Resource Conservation Recovery Act. She is an environmental engineering graduate of Benedict College.

Toy, currently a senior at the University of Tennessee majoring in nuclear engineering and minoring in nuclear security, has been involved in undergraduate research and has held internships with Consolidated Nuclear Security and Southern Nuclear.

Moderator comments: Wes Hines, UTK nuclear engineering department head, acted as moderator, opening the event by noting that the panel was “something we've been wanting to organize for quite some time.” The in-person event was simultaneously webcast; about 50 students from different areas of Tennessee were in the audience. He continued, “This panel is being offered today in collaboration with our University of Tennessee Tickle College of Engineering Engineers Day. . . . The goal for this session, at least for the audience, is to host some panelists that have some diverse experiences, and they're going to share these experiences with you, share tips and tell you their stories in the hopes that you can learn from them and maybe visualize yourself as being the successful panelists in the future.”

Harold T. Conner: Conner began his presentation by telling the audience that he was from Martin, Tennessee, “that little town right on the border, about 50 miles away from Jackson and probably a couple of hours north of Memphis.” Speaking about the positive influences that he experienced during his youth, he said, “I had a mom that was a second-grade teacher, and my dad was the principal and a 10th grade science teacher. So, I couldn't get away with anything at home or at school. I had to deal with the parent thing at school. And, really, that's kind of why I ended up in engineering. My dad was a chemistry teacher in high school, and physics and math. And, so, I got interested in all those things when I was coming up as a young child. . . .

“Many of you will have an opportunity to be exposed to educators, the communities, your churches, and others that will help direct your path. . . . I had teachers that prepared me. I had Mrs. Moore, Miss Armstrong, my dad. Harold Conner and Florence Conner [his parents] and others that paved the way for me and gave me the vision of doing the best I can in my life.”

He began his studies at the University of Tennessee in his hometown in 1963. “The University of Tennessee–Martin was, like, two blocks away from where I grew up. But guess what? There were no black students at the University of Tennessee–Martin. It was completely and totally segregated. And in 1963, here comes Harold, going to matriculate at the University of Tennessee.”

He talked about the stress that he experienced in college. “In those days, I had a huge afro. . . . You know, I had a bunch of hair, and I thought I was going to change the world. I got to college and I found out, hey, things are different here. . . . I'm thinking I'm cool. But then, after I started taking graphics and statistics and trig and the preparatory courses for starting my chemical engineering degree, the pressure mounted and it was like, where did the hair go? So it started falling out. Actually, it did fall out, at 18, I guess. But it grew back. I got my afro back, but there was the stress and strain of being this first little black boy in this University of Tennessee.”

He continued, “People ask me, well, how did you deal with that? . . . And the thing that I remember the most is the friends that I made, the instructors, all the people I collaborated with. You just learn to deal with it. People say, how was it? How did you make it? Well, like you're doing now, sitting around the room with people that you loved, relationships that you built, and doing things together. And so, I made it through that start.”

Conner also offered early-career advice for attendees, based on his own experiences. “The co-op experience is something you ought to think about—you know, where you go to school a semester and go to work for an industrial entity the other semester, and it gives you a chance to be exposed to an industrial entity at the same time when you're taking your classes on campus. I offer to you, that's a great way to get your education. You get the experience, and, yeah, you can probably be hired by that company when you finish college. So, I had a chance to get that experience as a co-op student working at the Oak Ridge National Lab and the K-25 site in Oak Ridge.”

Conner’s career took off after that. “I ended up working all around the country, and from this little black kid that integrated the University of Tennessee–Martin, to supervising and leading several thousand people in many parts of this country. The thing I would say to you as you consider engineering at the University of Tennessee and beyond is to be collaborative, work in teams regardless of nuclear or chemical or electrical, mechanical, biomolecular, molecular, whatever you choose, you will have to work as a team. Much like your family unit, much like your high school. When you get out into the industrial world, you will be uniquely part of the team.”

Dari Gabriel: Gabriel also shared stories from her hometown and early education. She said, “I'm originally from Houston, Texas, but I graduated from Benedict College in Columbia, South Carolina. How I got there: Does anybody know about AAU [Amateur Athletic Union] basketball? I started playing in, like, third grade. Played all the way through high school, of course. So, I chose Benedict because that was pretty much the only school that offered me a full [scholarship] for academics and sports. Whether it was academics or sports, the coach wanted me there. He was like, choose either one, but I want you to come play for our team.” During her junior year of high school, she realized that she wanted to pursue engineering. Gabriel continued, “So, that was a great opportunity. Benedict had engineering. They had, at the time, electrical, computer engineering, environmental, and computer science.”

She talked about her struggles early in college. “I had the toughest time my freshman year, trying to juggle time management, [with] basketball practice—we had practice like two, three times a day—and then you still had class throughout the day. The coaches, they're like, you know, you still have to be here on time. The teachers are like, you know, I still got class. So I was trying to make both people happy. Long story short, I stopped playing ball my sophomore year because I just came to a point where I had to choose which one was going to help me be more successful . . . which one would make me more money, playing in the WNBA or being an engineer. Of course, being an engineer! But, you know, I still have hoop dreams. I play now and then.”

She continued, “So, I started off in electrical after that, that first semester, but I knew that that was not my type of engineering. I went to my advisor. He honestly had no clue what he was doing either, because he had me doing my own schedule at the time. But, anyway, he accidentally put me in environmental engineering and I was like, you know, I've never heard of this before, but I'll try it. I'd say, my first day of class, I fell in love with it. I was like, this is it. I just had that feeling. I think I pretty much enjoyed it because I've always been like this type of person to want to help the Earth and help people out and do more.”

She spoke too of helpful guidance from her mother. “When I stopped playing ball my sophomore year, my first mind was to switch schools because I so honestly wanted to play. But, my mom, she was like, well, you used the ball to get to school. So now that you're there and you have great teachers around you, I don't think you should leave that. It took a lot of thoughts and prayers, but, of course, I ended up staying, and it definitely worked out for the best.”

Gabriel told the audience how she began her career at UCOR—thanks in part to her fellow panelist, Harold Conner. "He came to Benedict my senior year, this February, to speak to us. I got an opportunity to intern with UCOR that summer, from May to August 11th, and then I was offered a full-time position that started August 15th. So, everything happened pretty fast, but I’m definitely blessed and grateful for the opportunity.”

Jasmine Toy: Toy began her story from the very beginning. “I am a Memphis product through and through,” she said. “I was born at the Germantown Hospital. Southland Elementary is in my neighborhood. Still, I went to Southwest as an elementary school kid. . . . In middle school, I never thought about doing STEM. High school is when I finally started thinking about doing STEM because I got a letter in the mail from East High School about their virtual STEM Academy. I did not want to do it. I hated math my entire life . . . My father told me, okay, you could try for a year. If you don't like it, we never have to do it again.”

She found that she liked the STEM program. “When I went to East High School's virtual program, it was fantastic. All the modules we had were amazing. But even then, I was not really convinced. And then my high school guidance counselor . . . she recognized that I had a lot of energy and that it was not being applied correctly. So, she informed me that UT was having a summer program for engineering students.” Initially skeptical of spending her summer “doing work,” she decided to attend. Pointing to the back of the room, she called out Travis Griffin, director of UT's Engineering Diversity Programs, saying he immediately “made me feel welcome, made me feel at home.”

Toy then spoke about how her interest in math, engineering, and physics received a boost from a movie. “Something amazing happened when I was in high school. There was a movie that came out called Hidden Figures. Before this in physics class, I was just the class clown. But when Hidden Figures came out, that really jumpstarted something in me where I thought to myself, I can do this. I got really focused in my physics book. I started really taking notes, and something that we had to do at the end of the semester, my senior year for our B exams, was create PowerPoints of the chapters of physics that we were going over, that were going to be on the exam. I was stuck with the nuclear section, which I knew nothing about. When I created that PowerPoint, I realized that it was interesting.”

She continued her story after her high school graduation. “I came in in the summer program, the intercollegiate summer bridge program [at the University of Tennessee]. That's where freshmen that are coming in can take classes, chemistry and math, with some of your other peers, diverse. So, you can form a cohort. That was the best thing that happened to me, because once I formed my cohort in my unit, those were the people that I would see in class. Those are the people I would ask for notes. Those are the people I would form study groups with. If it wasn't for the people that I met and some of the programs that the Tickle College of Engineering has put together, I would not have made it through some of my classes. We studied together, did projects together.”

In speaking more about her experiences with math and the people she surrounded herself with, she said, “In another unconventional route, something that my cohort helped me with, was I did not have the ACT score to start immediately in calc 1. This was really discouraging for me just because I did everything I could for my ACT score, for my math score to come up. That just didn't happen. For all you out there that are really trying on ACT, do your best. But if it doesn't work, you can always maneuver around it. I took pre-calculus, passed it, but because I was taking pre-calculus, I could not take my engineering physics with that math class. I had to be in calc 1 to take my engineering physics. So, I had to completely delay starting my engineering track to get through my core basics.

“This is a step that a lot of engineers will skip and will rue the day because of it. Starting in pre-calc was the best thing for me because it gave me the tools I needed when I got to calc 1. It trained me in the concepts that I was going to need in college math, instead of just relying on the math that my teachers taught me in high school.”

Toy next told the audience about another challenge she faced: “My second semester sophomore year, I started to realize that when I was in class, I was not able to pay attention. I couldn’t focus. I wasn't getting a lot of notes. And my grades got significantly worse. I'm starting to think to myself, what is the issue? What's the problem? This is where my cohort came in and became really important, because they helped me through a lot of that, whether it was studying or taking notes, they helped me a lot. Through this process, I was able to be accurately diagnosed with my learning disability, ADHD [attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder].

“Being diagnosed with a learning disability when you're 20 is not for the weak. It was a hard road to get back to where I needed in order to be an efficient college student. But throughout this process, there is nothing like adversity to show you who you really are. When I think back to that moment, it's always funny to me because I legitimately thought about dropping out. I thought about going back home and going to Memphis and, like, getting a FedEx job. I was over it. But through not only the strength of my parents, who supported me a lot through the process, not only Mr. Griffin, who supported me a lot through the process, but also my sorority. My sisters helped me a lot through the process. I was able to get accurately diagnosed and helped when I needed to be.”

Toy concluded, “If I could say one thing to end this, I will say adversity is always coming and it always looks like you can never do it, but always use the help that's available to jump over your obstacles and not hold you back.”