How is Cold War–era radiation shaping the nuclear conversation today?

The Manhattan Project may have begun more than 80 years ago, but it’s still in the news—and not just because of Oppenheimer’s recent haul at the Academy Awards. On March 7, the Senate passed S. 3853, the Radiation Exposure Compensation Reauthorization Act, by a vote of 69 to 30, sending the bill to the House. It’s Sen. Josh Hawley's (R., Mo.) second attempt to reauthorize the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA)—which was first enacted in 1990 to address the legacy of U.S. nuclear weapons production—before it expires in June. The bill would extend the deadline to claim compensation by five years and expand it from the dozen states now covered to include individuals exposed to radiation in certain regions of Missouri, Alaska, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

President Biden signed an executive order in 2022 extending RECA for two years. The White House indicated in a March 6 statement that Biden would sign the RECA reauthorization act into law if and when it reaches his desk, but similar legislation—in the form of an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act passed by the Senate in July 2023—was cut from the NDAA in December 2023 during Senate and House conference negotiations.

Hawley is on a campaign to get a RECA reauthorized—this time even sending a letter to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in January urging them to recognize “the victims of America’s nuclear testing” during the televised Academy Awards. Setting aside the Beltway rhetoric and Hollywood hype, what do you need to know about this legislation?

Hawley’s quest: Hawley has been demanding attention for radiation exposure from Cold War–era uranium processing and resultant waste in Missouri, and in February 2023 he introduced bill S. 418. Known as the Justice for Jana Elementary Act of 2023, it would have provided money for cleanup and investigations for an elementary school in the St. Louis area that has been involved in an ongoing controversy surrounding elevated levels of radioactive contamination found in areas near the school, which is in the flood plain of Coldwater Creek. The creek was contaminated by waste produced from uranium ore processing activities conducted by Mallinckrodt during the 1940s and 1950s that was improperly stored at the St. Louis airport and another site near the creek. While the bulk of the waste has been removed, some residual contamination remains.

S. 418 was passed by a voice vote in April 2023 but did not move forward in the House. It was a few months later, in July, that Hawley introduced his RECA reauthorization amendment to the NDAA—a bill that could see some of his constituents eligible for compensation payments.

RECA facts: RECA only covers historical radiation exposures related to World War II and Cold War–era nuclear weapons activities in the United States. As implemented by the Justice Department, the act allows those affected by specific radiation exposures from 1942 to 1971 who developed specific health conditions to claim compensation from the federal government.

RECA has five claimant categories: uranium miners, uranium millers, and ore transporters; on-site nuclear test participants; and people who lived downwind from the Nevada Test Site (known as “downwinders”). To be eligible for a payout of $100,000 (for uranium miners, millers, and ore transporters), $75,000 (for test participants), or $50,000 (for downwinders), a claim (which can be submitted by the affected individual or by his or her descendants) must prove the individual was a resident or was present in a particular location at a particular time and developed one of several specific illnesses.

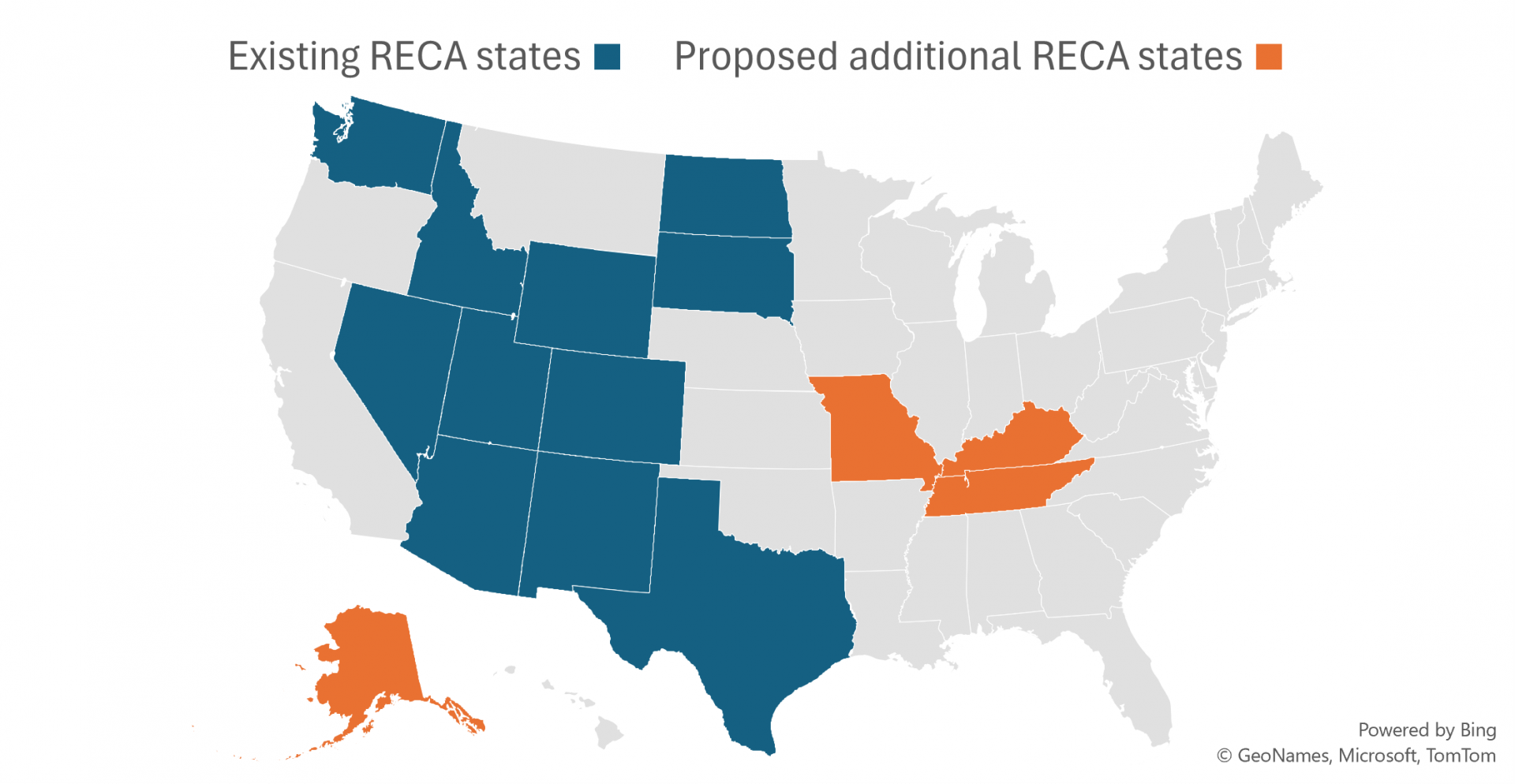

RECA was passed in 1990 and broadened in 2000. By 2015, the Justice Department reported that a total of over $2 billion in compensation had been awarded for 32,000 approved claims; between 1990 and 2015, a total of nearly 43,000 claims were filed. Currently, RECA includes portions of 12 states: Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Wyoming, South Dakota, Washington, Utah, Idaho, North Dakota, Oregon, Texas, and Nevada.

If the RECA reauthorization bill passes and is signed into law, parts of Missouri, Alaska, Kentucky, and Tennessee will be included in the act, and coverage for radiation exposure from nuclear weapons testing, including the Trinity Test in 1945 and testing in Guam, would be expanded. People affected by radiation in both the new coverage areas and areas previously covered would have five years to file claims. The AP has reported that according to Hawley’s office the cost of the RECA reauthorization bill could be about $50 billion.

“Nuclear” is an adjective: Nuclear weapons and nuclear energy are as different from one another as basket weaving and basketball. Yet this obvious fact bears repeating. That much is clear when media reports conflate nuclear weapons—or in this case compensation for radiation exposure due to the nation’s early production of nuclear weapons—with nuclear energy and the nuclear fuel cycle.

Coverage from Axios of Hawley’s RECA reauthorization bill, for example, included the statement that “The energy transition will emit lots of radiation—and many are still suffering health problems from the last industrial age.” Just how a “transition” can emit radiation was not explained, but there is a bigger problem here than vague language: the conflation of nuclear energy as a clean power source with historical nuclear weapons programs.

Let’s not stop there: We need to be clear that this bill is meant to protect people from radiation exposure resulting from historic nuclear weapons production—not nuclear power, which safely generates roughly 40 percent of the United States’ clean power. It’s important to also remember:

Times have changed—If RECA is reauthorized, it will still only cover radiation and radioactive contamination from the Manhattan Project, when the nation swiftly harnessed science and engineering in the service of national defense and developed the first nuclear weapons, and ensuing Cold War weapons production and testing.

It does not and will not have any effect on nuclear energy generation: past, present, or future. Nor do nuclear power plants, regulated by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and safely operated by commercial power companies for decades, generate the improperly controlled waste products that the Manhattan Project did 80 years ago.

Correlation is not causation—Importantly, RECA does not require claimants to prove that their illness was caused by radiation exposure—only that they were in a certain area at a certain time and developed a covered health condition—regardless of other risk factors. That would be the case for the reauthorized RECA as well.

Nearly 30 years after RECA was initially passed, there are still more questions than answers about the health effects of radiation, especially at low doses and low dose rates—close to background radiation doses—like those that have Sen. Hawley’s St. Louis constituents concerned today.