Observations on U.S. nuclear export control policies

Having recently attended a Pillsbury and Nuclear Energy Institute seminar on "Export Controls for the Nuclear Renaissance," it became clear to me why the United States is losing its leadership position in nuclear energy: The bureaucracy is winning the war over effectiveness of policy and nonproliferation.

Having recently attended a Pillsbury and Nuclear Energy Institute seminar on "Export Controls for the Nuclear Renaissance," it became clear to me why the United States is losing its leadership position in nuclear energy: The bureaucracy is winning the war over effectiveness of policy and nonproliferation.

The Atomic Energy Act of 1954 was written at a time when we were the dominant nuclear technology owner and efforts were made to keep it so. In the last 57 years, much has changed in that landscape that makes this law, as it pertains to export controls, ineffective in restraining the proliferation of nuclear weapons, but also in America's ability to compete in the world market.

What did I learn at this meeting? I learned that we have a set of laws and regulations that are not even clear to the enforcers. Who are the delegated agencies responsible for export controls? Quite a few: the U.S. Department of Commerce's Export Administration, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the Department of Energy's National Nuclear Security Administration, and the State Department.

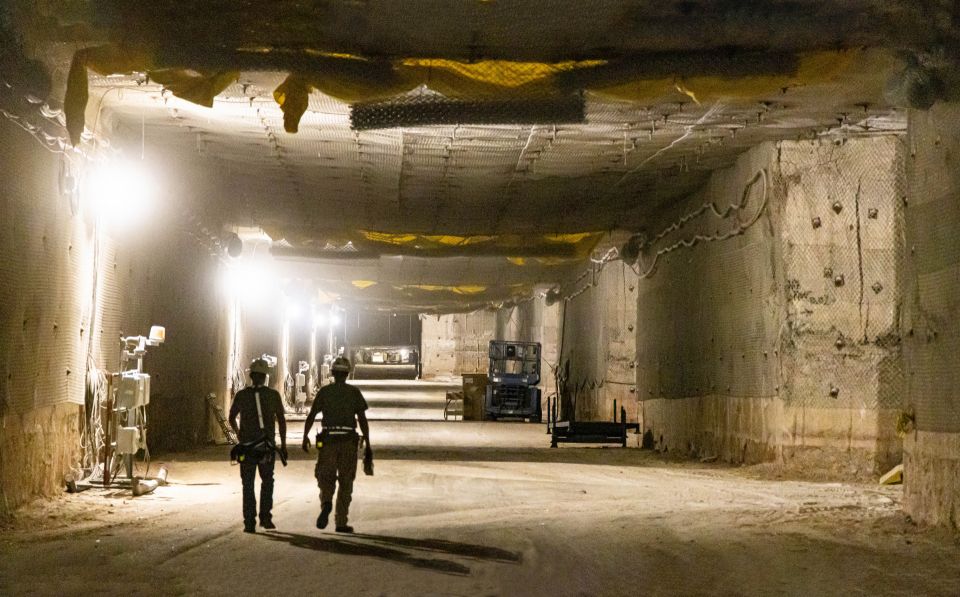

If that was not enough, the nuclear island and the balance-of-plant operations are separately regulated as are the scientists' and engineers' ability to speak to each other. The additional requirements under the complicated regulatory regime include obtaining 10 CFR Part 810 approvals from the DOE, 10 CFR Part 110 approvals from the NRC, and compliance with Commerce Department export regulations found in 15 CFR Parts 730-774.

If that was not enough, the nuclear island and the balance-of-plant operations are separately regulated as are the scientists' and engineers' ability to speak to each other. The additional requirements under the complicated regulatory regime include obtaining 10 CFR Part 810 approvals from the DOE, 10 CFR Part 110 approvals from the NRC, and compliance with Commerce Department export regulations found in 15 CFR Parts 730-774.

Navigating the export control regulatory maze

Even before we can sell our products and services to a nation and begin to navigate the maze of export control agencies and regulations, we must first obtain congressional approval according to Section 123 of the Atomic Energy Act. This poses an additional restriction and burden on our companies that other nations do not have. These congressional and State Department approvals are being used to extract perceived nonproliferation benefits while other nations have no such restrictions. This deters nations that are Non-Proliferation Treaty signatories from dealing with U.S. firms since they have other options where no such pressures exist, which again denies U.S. firms access to markets.

While the goals of nonproliferation policy are laudable and needed, the bureaucracy established to implement these laws is not. We are at a point where U.S. participation in the world nuclear expansion is diminished, allowing other nations to be faster in granting approvals to work with other nations by implementing equally effective nonproliferation policies.

While the goals of nonproliferation policy are laudable and needed, the bureaucracy established to implement these laws is not. We are at a point where U.S. participation in the world nuclear expansion is diminished, allowing other nations to be faster in granting approvals to work with other nations by implementing equally effective nonproliferation policies.

What is missing is common sense. What is needed is a rewrite of legislation to eliminate centers of delay to allow the United States to compete and affect nuclear expansion on a world scale. The limitations imposed on training and information exchange are at best archaic and totally contrary to expanding our influence to the development of safe nuclear energy for peaceful purposes.

Top-down review of effectiveness and cost needed

What is needed is a top-down review of the effectiveness and cost, both in compliance and loss of opportunities, of U.S. export controls policy and its implementation. The objective of this review should be to find a way to implement the policy more efficiently with true value-added elements to allow for more U.S. companies to compete and at the same time be more effective. The American Nuclear Society, at its November 2011 meeting, will explore this issue in greater detail to answer the bottom line question:

How effective are U.S. export controls at preventing the spread of nuclear weapons?

Kadak

Andrew Kadak is a past president (1999-2000) of ANS and advisor to the ANS Special Committee on Nuclear Non-Proliferation. He is a Professor of the Practice in the Nuclear Engineering Department of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He is a contributor to the ANS Nuclear Cafe.