It has been 100 years since Payne-Gaposchkin first upended scientists’ understanding of astrophysics. She continued on a groundbreaking career as an astronomer and academician, leaving it to others, including today’s would-be fusion power plant developers, to figure out how to fuse hydrogen isotopes to build “stars” on earth.

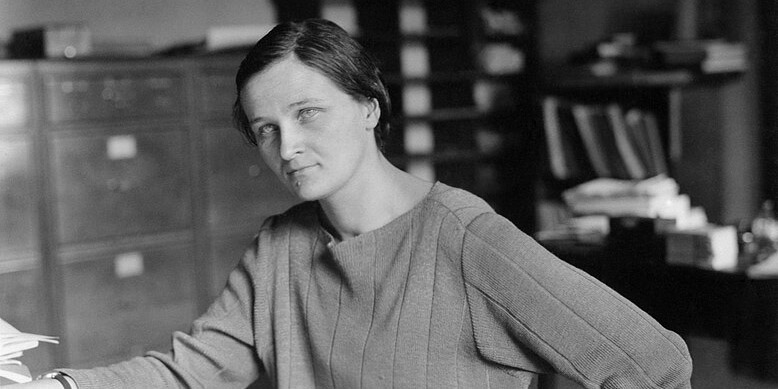

Early years: Cecilia Payne was born in rural England in 1900, and as a child she had a penchant for science. After first studying botany at Cambridge University, she turned to physics, but then—after attending a lecture by astronomer Arthur Eddington on his recent expedition to observe the 1919 solar eclipse in an effort to prove Einstein’s theory of general relativity—she pivoted to astronomy.

A stellar thesis: Drawn to Harvard University with the welcome of Harlow Shapley and supported by a graduate fellowship for women, she studied Harvard University’s large collection photographic glass plates of stellar spectra. Her work is described in Cosmic Horizons: Astronomy at the Cutting Edge, edited by Steven Soter and Neil deGrasse Tyson, as a publication of the New Press, and excerpted by the American Museum of Natural History.

Because Payne-Gaposchkin had studied quantum physics, she realized that the spectrum of an atom could change at high temperatures, becoming ionized with electrons stripped away. After long hours working late into the night to analyze heavy glass photographic plates, she found that in the Sun and other stars, elements heavier than helium account for less than two percent of the mass of stars. Payne-Gaposchkin produced a Ph.D. thesis that was the first awarded for work at Harvard College Observatory, titled “Stellar Atmospheres: A Contribution to the Observational Study of High Temperature in the Reversing Layers of Stars.”

According to Cosmic Horizons, “Payne showed how to decode the complicated spectra of starlight in order to learn the relative amounts of the chemical elements in the stars. In 1960, the distinguished astronomer Otto Struve referred to this work as ‘the most brilliant Ph.D. thesis ever written in astronomy.’”

Proven correct: Payne-Gaposchkin’s conclusions were initially rejected by influential astronomers at the time, who believed that the stars were made of roughly the same elements as Earth, and, though she never doubted her own data, she was persuaded to publish her thesis with a statement that her calculated masses of hydrogen and helium were “almost certainly not real.” Within a few years, however, she was proven correct.

Despite being subject to discrimination as a female scientist throughout her education and career, in 1956 Payne-Gaposchkin ultimately reached two other firsts: She was named Harvard’s first female professor and first female department chair. A wife, mother of three, and celebrated scientist, she died in December 1979.