The U.S. and U.K. are both investing in HALEU. How do the programs compare?

A plan to build up a high-assay low-enriched uranium fuel cycle in the United Kingdom to support the deployment of advanced reactors is still in place after the Labour party was voted to power on July 4, bringing 14 years of conservative government to an end. A competitive solicitation for grant funding to build a commercial-scale HALEU deconversion facility opened days before the election, and the support of the new government was confirmed by a set of updates on July 19. But what does the U.K. HALEU program entail, and how does it differ from the U.S. HALEU Availability Program?

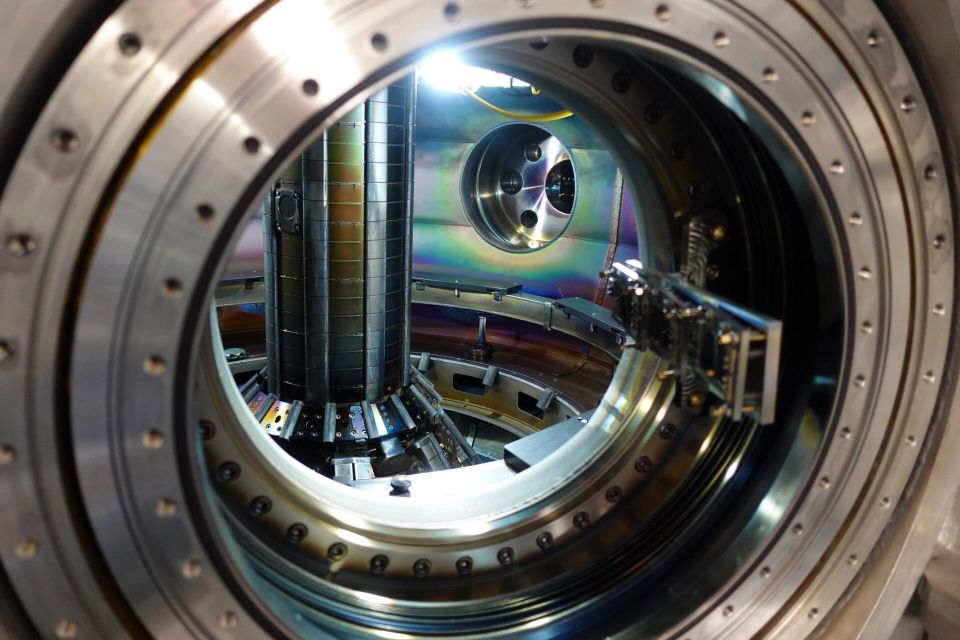

Inside Urenco’s Capenhurst enrichment facility in the U.K. (Photo: Urenco)

Money for HALEU: The U.K. Department for Energy Security and Net Zero announced an investment of £300 million (about $383 million) in HALEU infrastructure in January, making the U.K. the first European country to move forward on HALEU enrichment and fulfilling in part a pledge made in December 2023 at COP28 with four other nations—the United States, Canada, France, and Japan—to collectively mobilize more than $4.2 billion in public and private funds for fuel security over the next three years.

On May 4, the government got more specific, announcing that £196 million (about $245 million) would go to Urenco, which is part-owned by the U.K. government, to build a facility that could produce enriched HALEU at the rate of 10 tons per year by 2031. That facility will be cited in Capenhurst, Cheshire, in the northwest of England, where the company already operates three enrichment plants that produce low-enriched uranium.

With enrichment funds allotted, the government next announced funding of up to £70 million (part of the £300 million announced in January) through a HALEU deconversion competition, seeking applicants to support the design and build of a commercial-scale oxide HALEU deconversion facility (and the design of a commercial-scale metal HALEU deconversion line that could be deployed within the same facility “in the event of market growth”). That competition opened to applicants on July 1 and will close September 9.

First comes oxide: Applicants who want to build a deconversion plant in the U.K. under the scheme must include a proposal to design, build, and commission a commercial-scale oxide HALEU deconversion facility that would be operational by 2031 with an initial processing capacity of at least 10,000 kgU (or 10 metric tons of uranium [MTU]) per year, and that can “allow for future expansion of production up to at least 30,000 kgU per year.”

The facility should be designed to support a future deconversion line that could produce HALEU fuel feedstock in metal form. (Some advanced reactors, notably sodium fast reactors, would require metallic HALEU fuel.)

While the deconversion solicitation makes it clear that the U.K. anticipates more need for oxide than metallic fuel, the application must include “at a minimum” a proposal for the detailed design of a commercial-scale metal HALEU deconversion facility, with a minimum capacity of 5,000 kgU per year. “Within the budget and time limits of the project, applications will be assessed on how far along the design process they will be able to progress, with additional scoring awarded to any bids that are able to go beyond detailed design,” according to the scheme guidance. The applicant must include a detailed plan for how deconverted HALEU in both oxide and metal forms would be packaged and stored.

Common ground: The United States issued requests for proposals for HALEU deconversion and enrichment in November 2023 and January 2024, respectively. Both the U.K. and U.S. programs divide the front-end fuel cycle tasks of enrichment and deconversion into separate funding arrangements, and both spell out plans for deconverting uranium hexafluoride into both oxide and metal fuel. Here are a few more similarities between the two programs.

Domestic focus—Each nation will only support enrichment and deconversion that takes place within its borders but is to some extent open to participation from allies. According to a set of clarification questions updated on July 19, deconversion applicants in the United Kingdom “must provide evidence of access to a U.K. site which has a license that covers the deconversion of HALEU and associated processes or provide a detailed plan for securing a U.K. site and/or obtaining the relevant planning permissions and site license, with specific timelines and qualified resource requirements identified for each step.” Grant awards can only be made to a U.K.-registered company, and proof of registration must be submitted as part of the application process.

Scale—The two plans are not that far apart on scale either. While a draft U.S. enrichment RFP released in June 2023 suggested would-be enrichers could provide quotes for a range of potential production quantities between 5 and 145 MTU of HALEU UF6 enriched to 19.75 percent U-235 during the 10-year contract period, the final RFP settled on 10 MTU of HALEU UF6 for its ask. (Importantly, awards may be offered to more than one enricher; the total contract ceiling for enrichment services is $2.7 billion for all task orders cumulatively awarded.)

Where they differ: While the United States is prepared to award “one or more” contracts for both enrichment and deconversion, U.K. plans to date only include support for one enrichment facility and one deconversion facility. Here are some more differences between the two programs.

Funding—Financial details of the U.K. government’s funds to support HALEU enrichment through Urenco were not released, but for its competitively awarded deconversion contract the U.K. will require “cofunding” for deconversion “at a minimum rate of 70:30 (government: industry)” and will not pursue any offtakes.

The United States, in contrast, eyed an offtake arrangement back in 2022 as it was setting up the HALEU Availability Program in a quest to spur demand and private investment in a sustainable commercial HALEU fuel infrastructure. The final U.S. RFPs for enrichment and deconversion call for indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity (IDIQ) contracts that will last up to 10 years, during which time multiple individual task orders could be issued.

U.S. metal parity?—While under the United Kingdom’s plan for deconversion HALEU oxide production would precede metal production (which is dependent on market signals), the U.S. deconversion RFP does not emphasize either oxide or metal. A “sample task order” included in the RFP “for evaluation purposes only” calls for equal production of oxide and metal: “The contractor’s receiving, transportation, deconversion and storage capacity shall accommodate the processing of up to 6 MTU of UF6 per year into 3 MTU of metal and 3 MTU of oxide.”

Schedule—The U.K. specifies when enrichment and deconversion operations are to begin (both by 2031), while the U.S. leaves the specific schedules for enrichment and deconversion up to the contractor. In the case of enrichment, “the schedule for completing this HALEU enrichment [task order] shall be defined in the offeror’s proposal. . . . HALEU UF6 product deliverables will be in accordance with the contractor-provided delivery schedule.”

The front of the front end—The U.S. enrichment RFP covers mining and milling, conversion, enrichment, and storage of UF6, while the U.K.’s announced award of enrichment funds to Urenco included no mention of mining, milling, and conversion.

A waiting game: In the United States, responses to the RFPs for HALEU deconversion and enrichment were due February 13 and March 22, respectively. Awardees have not been announced.

On June 27, the U.S. Department of Energy opened another RFP—this time for low-enriched uranium that “will meet the specifications for LEU fuel feedstock that is utilized by commercial light water reactors.” LWRs are typically licensed to use LEU enriched up to 5 percent, but some are testing fuel with slightly higher enrichments. the DOE plans to award two or more contracts for up to 10 years to buy LEU generated by new sources of domestic uranium enrichment capacity, which can include new enrichment facilities or projects to expand the capacity of existing facilities. Responses to that RFP are due August 26.