Senators probe global competition in fusion energy deployment

Hours before the Senate Committee on Environment and Natural Resources (ENR) opened a scheduled September 19 hearing on fusion energy technology development, CNN published an article titled “The US led on nuclear fusion for decades. Now China is in a position to win the race.” The article was entered into the hearing record, but senators had already gotten the message.

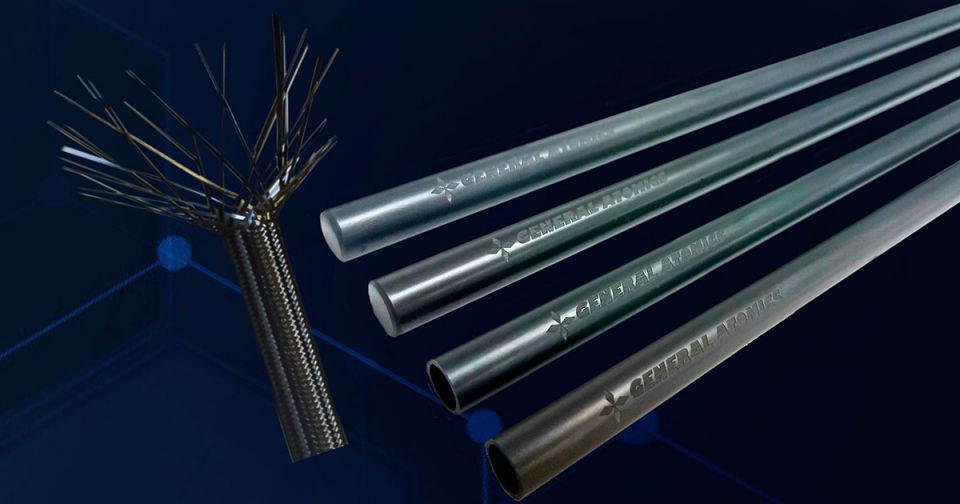

“China has recently mimicked our own U.S. strategic plan for developing fusion energy and is rapidly building out their research program and labs, modeled after our own DOE national labs,” said ENR chair Sen. Joe Manchin (I., W.V.) in his opening statement. “And China is not only trying to beat us in the science, they are also working to corner the fusion energy supply chain by securing the market for critical materials needed to build fusion power plants.”

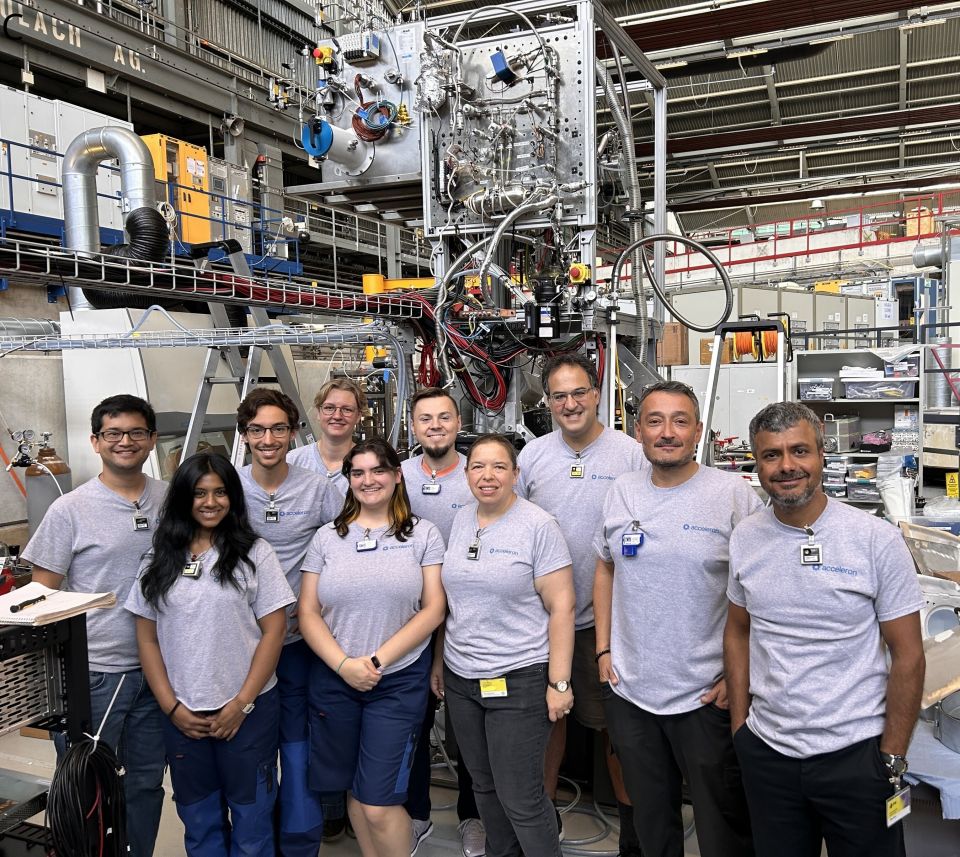

The senators probed the timeline for fusion energy deployment and supply chain needs after hearing from three invited witnesses: Jean Paul Allain, associate director of the Department of Energy’s Office of Fusion Energy Sciences; Jackie Siebens, director of public affairs at fusion developer Helion Energy; and Patrick White, research director at the Nuclear Innovation Alliance.

The inside joke–turned-cliche that fusion is always a decade away made an appearance, but this time in a conversation that acknowledged that if commercial fusion energy within five years is possible, now is the time to secure the fusion supply chain.

China: According to press reports, including the CNN article and a July 8 Wall Street Journal article that was referred to by ranking member Sen. John Barrasso (R., Wyo.) in his opening statement, China is developing technologies and plans originating in the United States—but is doing it faster.

Siebens confirmed those reports when she said, “One company launched a direct copycat program pursuing Helion’s design, and another publicly stated its intent to replicate key aspects of Helion’s approach. We've seen it before, in solar and batteries, where the U.S. pioneered breakthrough technologies only to lose out to China in the race to mass deployment. Without a comprehensive U.S. response, we risk being outpaced by China again.”

China has a demonstration plan, White said, and “they're also completing a facility that will lead cross-cutting fusion research and development for key materials fuel cycle technologies and commercial systems. The Chinese plan shows both an understanding and a commitment to the scientific, engineering, and commercial steps necessary to get fusion energy onto the grid.” They not only have a plan, “they’re executing on it,” he added.

On timeframes: Allain testified to DOE-FES’s work with fusion energy developers on public-private partnerships and its recent publication of a vision and strategy, to be followed by a national fusion science and technology road map. Pushed to say when the United States could see a commercially viable plant in operation, Allain said what DOE-FES is “really focused on right now is making sure that the science and tech gaps that we do have on some of these approaches are addressed right now, right in the decadal time frame. That's been the focus we're looking at, in the 2030s for us to be able to see those fusion pilot plants,” Allain said. “We are making strides and being able to close those gaps, and we see that in the next half decade to decade.”

Siebens’s answer was more specific. Helion, which is developing a pulsed fusion technology with deuterium and helium-3 fuel, has operated six prototype machines over 11 years, she said. Now, the company is building a prototype called Polaris that it expects to operate this year. Polaris will “be the first machine to demonstrate electricity production. Following Polaris, we will construct the world's first commercial fusion power plant, backed by a power purchase agreement with Microsoft.”

Manchin would like to see Helion carry out plans to collocate a 500-MWe fusion plant with a Nucor steel facility in his home state of West Virginia. But before that can happen, Helion would have to build that first commercial plant for Microsoft—a 50-MWe facility Helion expects to bring on line in 2028 under a power purchase agreement with Microsoft signed in 2023.

Given that grid-scale commercial fusion power in 2028 “would be more than a decade before ITER, [that] almost seems too good to be true,” Manchin said in his opening statement.

While Helion might be an outlier on timeline (and fuel type and technology), more than 40 fusion developers want to achieve commercial fusion. White offered a set of development phases to “enable more meaningful comparison between the fusion energy concepts at different phases of development.” Those four phases are scientific demonstration (net energy gain), engineering demonstration (consistent power production), commercial demonstration (integrating commercial systems), and wide-scale commercial deployment.

“Fusion commercialization will require private companies to complete all four phases, but company-specific pathways may differ. Some concepts may be completed under a single demonstration phase, with one machine serving as a scientific and engineering and a commercial machine,” he said, adding that “ultimately, the proof will be in electrons on the grid.”

More on Helion’s goals: Barrasso questioned Siebens on Helion’s goal for demonstrating electricity production with its Polaris machine now under construction, given that just a few months remain in 2024.

“We are on track to complete construction of this plant this year and begin testing likely this year and then continue that through next year,” she said. “And yes, this is the machine that we believe will demonstrate electricity production.”

Barrasso asked if Microsoft’s power purchase agreement “includes a firm deadline” with financial penalties if goals aren’t met. Siebens confirmed it did. “For 2028, we need to have the plant constructed and begin operations and then reach full commercial operations, providing electricity to Microsoft in 2029,” she said.

In response to a question on electricity costs from Sen. Angus King (I., Maine), Siebens said that for the Microsoft and Nucor agreements, “we're going to be at market rate or below.” In the longer term, if Helion is “able to mass produce this on the scale we envision, which could ultimately be building one generator a day, we could reduce cost down to 1 cent per kilowatt-hour, which is truly world changing,” she added.

“I’m delighted to hear that,” King said, “but I still remember when the prediction in the ’50s for nuclear power was that it would be too cheap to meter. So, go for it.”

U.S. government role: Allain testified to DOE-FES’s approach to a bold decadal vision built on three actions: closing critical science and technology gaps, establishing and leveraging public-private partnerships, and building a robust fusion technology manufacturing network.

Siebens suggested that adapting existing government programs to include fusion, such as the DOE’s Loan Programs Office, the 45X manufacturing production tax credit, and the CHIPS and Science Act, would be a good place to start. “But eventually we also need to develop a new bold program for fusion. . . . It should include strategic manufacturing support to provide significant funding to build out the manufacturing capacity necessary for large-scale fusion deployment and move the U.S. toward applied materials R&D.”

“Fusion materials is a perfect place for the federal government to take a lead,” White agreed. Developing data, creating test facilities for materials research, and neutron radiation of materials to “help develop and really optimize new alloys is critical to ultimately creating materials that can help facilitate the safe and economic production of fusion power, and that's something where it might be too large of a lift for any one private fusion company to take on,” he said.

“We see the real race here beginning after we actually demonstrate and deploy that first machine,” Siebens added. “We're already watching China work aggressively to lock down that supply chain.”