Disney World should have gone nuclear

There is extra significance to the American Nuclear Society holding its annual meeting in Orlando, Florida, this past week. That’s because in 1967, the state of Florida passed a law allowing Disney World to build a nuclear power plant.

As bizarre as that sounds, it is more of a testament to the political power the Mouse had than anything nuclear. This was 1967. While the Atomic Energy Commission was up and running, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the Department of Energy, and the Environmental Protection Agency were all dreams yet to come. Their formation changed everything about the industry. So this law is just an interesting historical footnote.

But it is also an example of how much of a visionary Walt Disney was. He was also impatient and understood how slow societies and governments move—and Walt wanted to move fast. He knew that his plan for the park would need lots of power, lots of flexibility, and lots of self-government.

Richard Foglesong described in his book Married to the Mouse how Disney had unusual political leverage because the state and the community around Orlando wanted very much for Disney World to be built. As he put it, “Disney wanted protection from government regulation.”

Epcot was central to Disney’s particular vision for the future. Epcot, or Experimental Prototype Community Of Tomorrow, was originally built to become a city of 20,000 as a test for futuristic city planning. Designed in the shape of a circle, businesses and commercial areas would be at its center, with schools, recreational areas, and community buildings around it. Residential neighborhoods would be on the perimeter.

Monorails, people movers, and small trains would provide the main transportation on the surface within the city limits. Automobile traffic would be underground for pedestrian safety.

Pretty awesome plan.

However, Disney could not realize his vision unless he had permission to be autonomous from the Florida government. What he really needed was his own private municipality. So, Florida gave Disney those powers usually reserved for county governments—the power to build roads and drains, levy taxes, issue bonds, and have emergency services.

For decades, Disney had a planning committee with complete authority. The rights granted to Disney by the state of Florida provided the park with immunity from the laws of surrounding communities. That changed recently when the state revoked Disney’s self-governing status. The two parties, however, have since agreed to the creation of a new board that will work on Disney’s development plans with the Central Florida Tourism Oversight District, which encompasses the 40-square-mile property that’s home to the Walt Disney World resort.

The nuclear angle was key to Disney’s futuristic plan for Epcot. He wanted this city to be self-reliant, and nuclear is the best way to do that. It was during an era more supportive of nuclear—more in need of big power and big dreams—and it wasn’t that long after Eisenhower’s Atoms for Peace initiative.

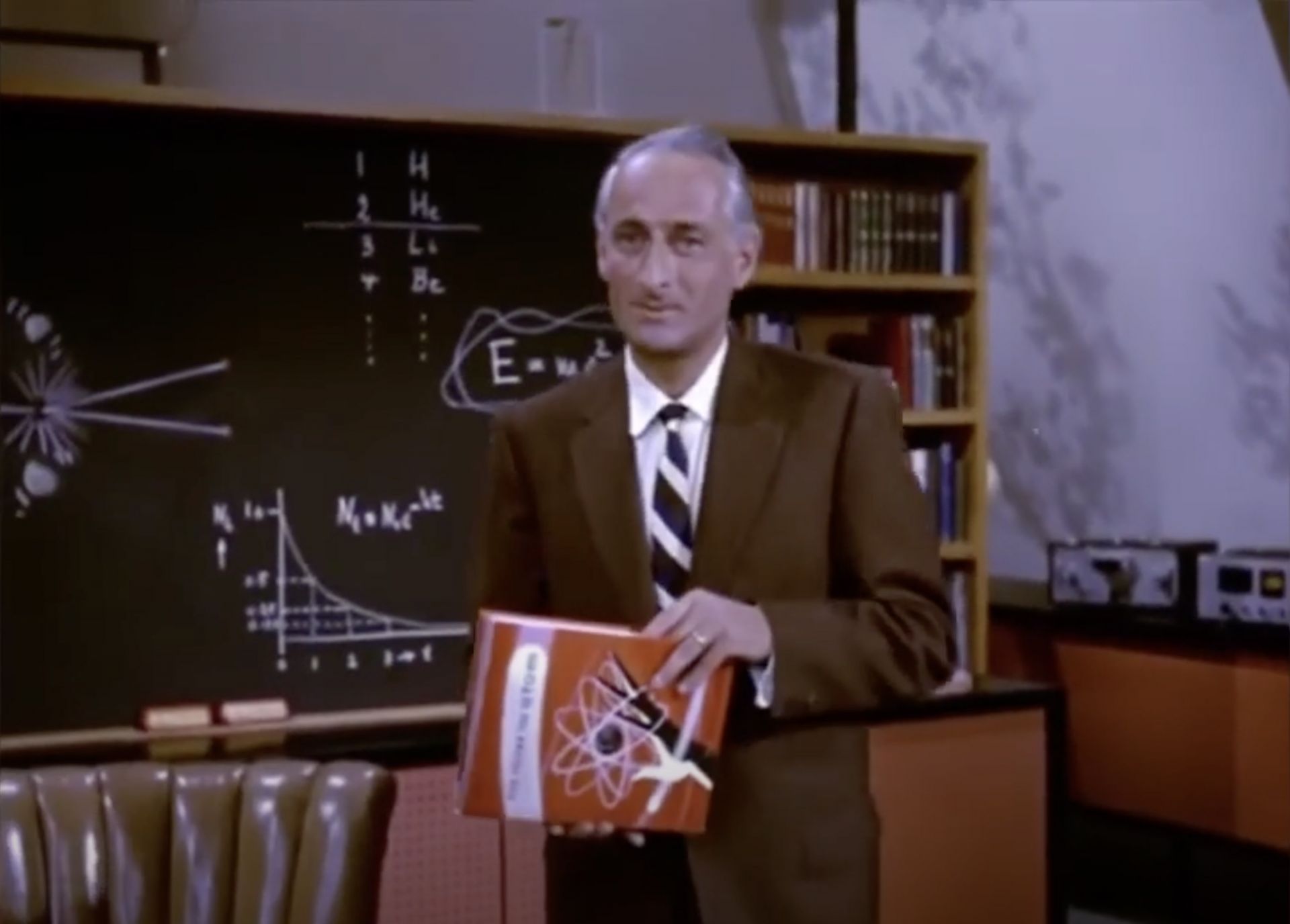

Heinz Haber, in a still from the “Our Friend the Atom” epsiode of Disneyland, holding the book the episode is based upon. (Image: Disney)

Disney even partnered with his personal science consultant, University of Southern California professor Heinz Haber, to write the 1956 book Our Friend the Atom. It was later condensed into a 1957 episode on the TV show Disneyland (which later went by the name The Magical World of Disney).

Thus, something like a small modular reactor of the kind currently being built by NuScale Power, X-energy, or TerraPower would fit right into a vision that also includes Tomorrowland. That’s because an SMR is the kind of thing Walt Disney himself envisioned for our future. Compact, can’t melt down, doesn’t even need to shut down to refuel, can operate for decades, the lowest emissions of any energy source, can ramp up and down quickly to load-follow their solar farms, and is cheaper than anything except gas—there is nothing that better represents the future of power in America or the vision of Walt Disney.

Of course, the present leadership of the House of Mouse has no plans to build nuclear. In place of the envisioned nuclear plant sits a gas-fired power plant.

Walt Disney World consists of 48 square miles containing hundreds of buildings that include world-class hotel and conference centers, theme parks and exotic ride adventures, and precisely controlled spaces for horticulture and animal care.

Something like NuScale Power’s small modular reactor plant is the right size for Disney World and would best fit what Walt Disney himself envisioned for our future. (Image: NuScale)

In addition to a lot of natural gas, Disney has been building a lot of solar. Their 270-acre, 50-MW, Mickey-shaped solar farm near Epcot Center is made of 48,000 solar panels and is operated by Duke Energy. Cinderella Castle’s holiday display of 170,000 lights has been painstakingly switched to LED lighting, reducing the amount of power needed to that required to operate four coffee pots.

Disney World’s total annual operating costs exceed $10 billion, requiring more than one billion kilowatt-hours of electricity and costing about $100 million a year. That’s the output of only two or so SMR modules and would be the most resilient and reliable power source for the park. In a state prone to extreme weather events that is threatened by rising sea levels, that is an obvious goal.

But it’s not like Disney World doesn’t presently use nuclear power. Florida has four nuclear reactors at two nuclear power plants run by NextEra Energy—one in St. Lucie County and one at Turkey Point in Miami-Dade County. They generate about 12 percent of the state’s power, some of which flows to the Magic Kingdom. But the state is still 74 percent natural gas.

So, while Walt’s kingdom is still powered mainly with fossil fuels, there is room to replace them with nuclear and renewables. He would have liked that.

Note: A previous version of this article was published in February 2019 on Forbes.com.