UMich leads Space Force institute on hybrid nuclear power and propulsion concept

Seeking spacecraft that can “maneuver without regret,” the U.S. Space Force is investing $35 million in a national research team led by the University of Michigan to develop a spacecraft with an onboard microreactor to produce electricity, with some of that electricity used for propulsion. But this spacecraft would not be solely dependent on nuclear electric propulsion—it would also feature a conventional chemical rocket to increase thrust when needed.

The newly formed Space Power and Propulsion for Agility, Responsiveness, and Resilience (SPAR) Institute brings eight universities and 14 industry partners—including Ultra Safe Nuclear (USNC) as reactor developer—and advisors together for what UMich calls “one of the nation’s largest efforts to advance space power and propulsion” in the service of national defense and space exploration.

Electric propulsion: Right now, most space propulsion is achieved with chemical rockets, which provide a lot of thrust but burn through fuel quickly—with the potential for “regret” if a spacecraft runs out of the fuel it needs to complete a mission or navigate to a secure location. Electric propulsion powered by solar panels eliminates the fuel supply problem if craft are deployed where they can catch the sun’s rays, but large solar panels are unwieldy and make moving a spacecraft relatively slow and cumbersome.

The International Space Station, for example, gets about 100 kW from solar arrays “the size of a couple of football fields,” said Benjamin Jorns, UMich associate professor of aerospace engineering and institute director in an October 16 news article from the university publicizing the SPAR award.

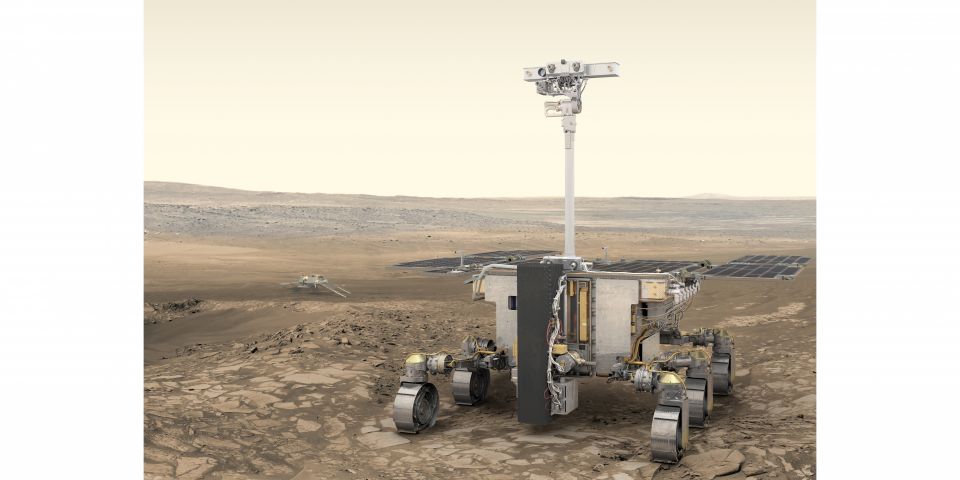

While such a massive array would not fit the space force’s needs, a 100-kW Hall thruster built at UMich demonstrates the potential of electric propulsion—if it’s connected to a compact and reliable source of power. That’s where a microreactor comes in.

SPAR’s reactor plans: Working within several subteams, university researchers and companies will collaborate to develop a lightweight microreactor, technologies that can turn the reactor’s heat into usable electricity, and engines to turn the electricity into thrust by ionizing a propellant and using electric fields to accelerate them to high speeds. One subteam will design the chemical rocket, and according to the above-mentioned UMich article, the team is trying to simplify fueling by demonstrating fuels that can be burned in the chemical rocket and also serve as an effective propellant for electric propulsion.

The U.S. Space Force announced the SPAR institute in mid-September after requesting proposals in January. At the center of the design is the onboard microreactor. USNC is set to develop a lightweight microreactor while engineers at UMich build a heat source to mimic the reactor’s thermal output and allow for testing of other power and propulsion components.

Not quite two weeks after University of Michigan announced the SPAR award, USNC filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on October 29, with plans to sell to a “stalking horse bidder,” Standard Nuclear Inc. USNC stated in a press release that it expects to “maintain full operational continuity” across its projects.

Converting thermal energy to thrust: SPAR subteams will work separately and together to design and test the hybrid rocket:

- From heat to electricity—Two teams will take different approaches: UMich and Spark Thermionics will investigate thermionic emission cells, while another UMich team will pair with Antora Energy on thermal photovoltaics.

- Radiating waste heat—Cornell University, Advanced Cooling Technologies, and Ultramet will design lightweight panels that can extract waste heat and radiate it out into space.

- Power processing—University of Wisconsin, UMich, and Cislunar Industries will design a power processing module to convert the electricity extracted from the microreactor so that it can meet the power demands of the electric engine.

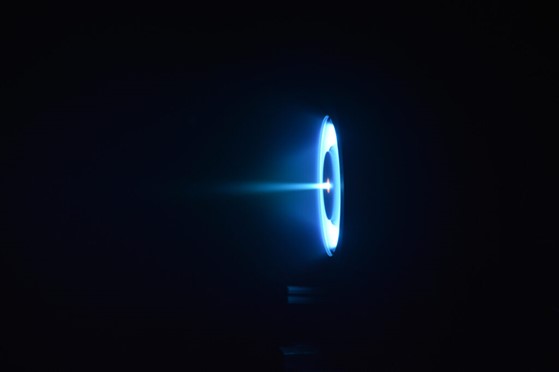

- Electric propulsion—Subteams will explore three different styles of electric propulsion: the Hall thruster approach of Jorns’s team at UMich, the applied-field magnetoplasmadynamic thruster (Princeton University and Champaign-Urbana Aerospace), and the electron cyclotron resonance thruster (University of Washington and NuWaves Inc.). Any of those thruster designs will rely on a module that turns the propellant into a gas, to be developed by Western Michigan University and Champaign-Urbana Aerospace, and a cathode to prevent the spacecraft from accumulating an electric charge by neutralizing the propellant, to be developed by Colorado State University.

- Chemical rocket—UMich and Pennsylvania State University will develop a “new approach,” and Benchmark Space Systems will provide an already developed commercial system for a proof-of-concept test.

- Modeling and diagnostics—Computer modeling and experimental diagnostics developed by UMich, Cornell, Colorado State University, and the University of Colorado will support the project, and Analytical Mechanics Associates will assess the full system.

- Advisory board—Northrop Grumman, Lockheed Martin, Westinghouse, and Aerospace Corp. are serving as advisors.

They said it: “The space force is tasked with securing America’s interests in, from, and to space,” said Joshua Carlson, space force program manager for SPAR. “We’re very pleased to work with University of Michigan, and their partners, just like we are for all our other efforts under the USSF University Consortium, as we seek to maintain the space force’s edge in great power competition.”

Speaking for UMich and the SPAR team, Jorns said, “We are very grateful to the U.S. Space Force and Air Force Research Laboratory for this opportunity. We’re excited to get started on this work with this exceptional national team.”

2x1.jpg)