Is Fukushima a teachable moment for nuclear educators?

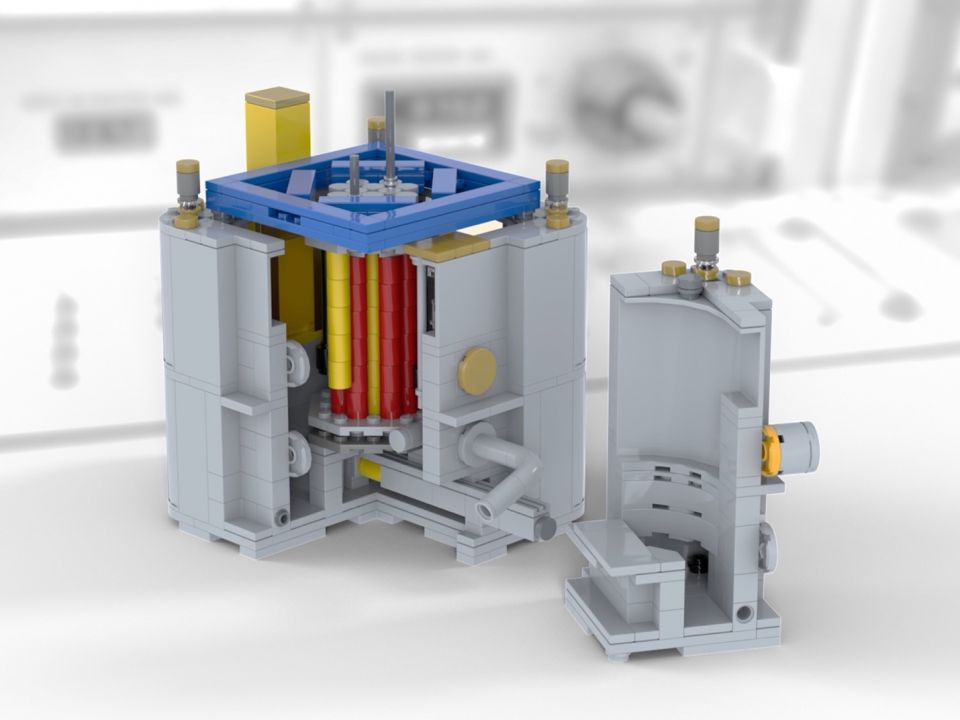

There are many facets of my chosen avocation as a pro-nuclear blogger and podcaster, but one aspect that has been prominent during the 25 days since the Japanese earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear nightmare at Fukushima has been that of atomic educator. Following the role model of my favorite teachers, I have worked hard to maintain a two-way flow of information-successful educators have to be open-minded learners. There is no doubt that I know a lot more about the design and operation of boiling water reactors with MK I containment vessels now than I knew four weeks ago.

Some nuclear energy advocates might cringe at my use of of the alliterative phrase of "nuclear nightmare at Fukushima," but I hope they will think hard about all of the implications of that choice of words.

Some nuclear energy advocates might cringe at my use of of the alliterative phrase of "nuclear nightmare at Fukushima," but I hope they will think hard about all of the implications of that choice of words.

It is hard to imagine a more nightmarish scenario than having a multi-unit nuclear power plant installation hit with a massive earthquake, a subsiding coast line, and a massive tidal wave that wiped out a significant portion of the local grid, the emergency diesel generators, and the electrical components required to enable even moderately difficult power restoration. Even the most ardent antinuclear activists with whom I have butted heads would have had to work hard to imagine that kind of initiating event.

Fukushima was truly a nightmare for those of us who favor the increasing use of nuclear energy as a way to reduce our rapid depletion of the earth's valuable store of hydrocarbons. It was pretty easy to recognize very early in the accident that it had the potential to be the story that the opposition to nuclear energy has been eagerly anticipating for many years.

Even the timing added to the bad dream quality of the event-there was already a steadily increasing drumbeat of reminders from organized antinuclear groups that an explosion and fire at a nuclear power plant had once killed people-25 years ago this month.

It is hard to imagine a worse situation than the one we faced on March 11, 2011. Not only were there vast areas of devastation and thousands of human casualties caused by the natural disasters, but there was also a highly visible nuclear power plant event. That nuclear event was occurring at the same time that hundreds of eager antinuclear Lilliputians had their updated media contact lists in hand. They were primed and ready to add as many more threads as possible to hold down the atomic Gulliver that they want us all to fear. The confluence of an event with an anniversary brought flashbacks of the incredible coincidence of a nuclear plant event occurring in Pennsylvania within weeks of the theater release of a movie about a core meltdown that actually included a line about causing damage to an area "the size of Pennsylvania."

The one thing that the professional opposition to nuclear energy had not counted on was the fact that information sharing today is on a completely different plane than it was the last time there was significant damage at a nuclear power plant. In April 1986, as in 1979, there was no Internet and no world wide web. Cable television was only available in very limited markets; CNN had finally broken into the public consciousness, but only a few months before Chernobyl when it was the only television news organization with live coverage of the Challenger disaster.

Within just a few hours of the earthquake and tsunami, informal networks of nuclear energy experts began exchanging information using the wide range of tools that modern communications technology has delivered. Though the initial headlines were breathlessly scary, there were alternative paths through which the real story could be gathered and shared. There was plenty of reason for concern among professionals, but it soon became clear that the many layers of protection and procedural backups were having a positive effect on the net outcome.

There will be lessons learned and additional protective measures implemented, but the fact remains that the loss of life at Fukushima Dai-ichi has been limited to two workers who were killed by the tsunami while performing rounds. One other worker was killed when a crane fell at the separate Fukushima Daini nuclear power station. In contrast to that very limited human toll, the natural disaster has killed in excess of 20,000 people.

As one of my favorite nuclear experts likes to point out, nuclear energy systems are designed to provide many opportunities to respond. Bad things can and do happen, but the basic engineering choices made from the earliest days of the technology were aimed at making sure that they happen as slowly as possible. Slow motion disasters might not be optimal from a public relations point of view, but they are often very beneficial from a public health point of view. It saves lives and property when there is time to take preventive action.

Though there have been many bad moments and plenty of negative press coverage, the accurate information that nuclear energy experts have shared using modern communications paths that include the web and social networks have begun to sink in. Despite all of the gloom and doom scenarios, each day brings us one step closer to stability and each report of injuries brings a growing recognition among the public that their carefully stoked fears regarding a nuclear catastrophe have been misplaced. Professional journalists have begun to recognize that the scary stories they told at the beginning were fictional instead of factual.

On Sunday, April 2, 2011, there was a front page story in the Washington Post titled Nuclear power is the safest way to make electricity, according to study. Similar stories are beginning to pop up in other unexpected locations, including The Guardian, The Australian, the New York Times, and even Treehugger.com.

I chose to enter the nuclear energy profession just two years after the Three Mile Island accident. It has not been the easiest choice I could have made. Young nuclear professionals who harbor a little concern about their future employment prospects can rest assured that Fukushima will not result in another three decade slumber. That is largely due to the efforts of people with real nuclear knowledge and the means, motive, and opportunity to share it widely.

Adams

Rod Adams is a pro-nuclear advocate with extensive small nuclear plant operating experience. Adams is a former engineer officer, USS Von Steuben. He is founder of Adams Atomic Engines, Inc., and host and producer of The Atomic Show Podcast. Adams has been an ANS member since 2005. He writes about nuclear technology at his own blog, Atomic Insights.