TVA's countdown to MOX fuel

The utility is assessing options to use it

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) could be one of the first nuclear utilities to accept mixed oxide fuel (MOX) from the Department of Energy (DOE) for use in its commercial nuclear reactors. The government is building a $4.8 billion factory in South Carolina that is scheduled to start producing MOX fuel assemblies by 2016 by blending weapons grade plutonium with uranium. The resulting fuel can be swapped out for regular uranium fuel.

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) could be one of the first nuclear utilities to accept mixed oxide fuel (MOX) from the Department of Energy (DOE) for use in its commercial nuclear reactors. The government is building a $4.8 billion factory in South Carolina that is scheduled to start producing MOX fuel assemblies by 2016 by blending weapons grade plutonium with uranium. The resulting fuel can be swapped out for regular uranium fuel.

The government's nonproliferation objective is to get 34 tonnes of surplus weapons-grade plutonium out of circulation forever. TVA's objective is to get nuclear fuel that will work safely in its reactors and at a competitive price.

TVA is a public power provider for a seven-state region serving nine million people. In 2010, 36 percent of its power generation came from nuclear energy. One element of its charter, which dates back to the New Deal programs between 1933 and 1936 of President Franklin Roosevelt, is to support national security missions. TVA built power plants to provide electricity for the Manhattan Project at Oak Ridge.

Today, it participates in the DOE's nonproliferation efforts through the use of fuel made from blended down highly-enriched surplus uranium.

Evaluating the potential for MOX

Mick Mastilovic, TVA's manager of Nuclear Fuel Supply, told ANS Nuclear Cafe in a telephone interview that the utility's evaluation of the potential for using MOX fuel will primarily address safety as well as economics of using MOX relative to all uranium fuel. TVA has not yet made a decision to pursue MOX fuel licensing and implementation.

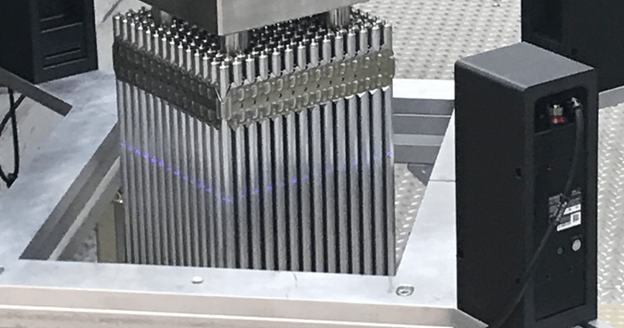

If TVA decides to use MOX, it could eventually replace up to 40 percent of the fuel assemblies in the cores of its Sequoyah and Browns Ferry reactors. The two Sequoyah reactors are pressurized water reactors with 193 fuel assemblies each. The three Browns Ferry reactors are boiling water reactors with 764 fuel assemblies each.

The DOE's MOX plant is expected to produce the equivalent of 1,700 PWR assemblies to dispose of 34 tonnes of surplus plutonium. At a projected output rate of up to 70 metric tons heavy metal per year, the MOX facility may produce more fuel than TVA's five reactors could consume.

The National Nuclear Security Administration and its contractor, Shaw Areva MOX Services, are working toward agreements to market additional MOX fuel through the fuel fabrication vendors operating in the United States: Areva, Westinghouse, and Global Nuclear Fuel Americas (GE-Hitachi).

TVA won't start out at the 40-percent core replacement level. The initial replacement level for the reactors will be about 8 assemblies of MOX fuel. Ramp up time to the 40-percent level depends on the DOE's production schedule, how well the MOX works, and cost factors, among others.

"There is nothing quick about the process, as we have many gates to go through before possible implementation," Mastilovic said, adding, "For instance, in the best case, we don't expect to be able to load MOX assemblies before 2018."

Explaining MOX to the public

One of the challenges that TVA faces is that the public perceptions of using plutonium as fuel needs some explaining. TVA starts by describing that MOX is a mix of uranium and plutonium. MOX has about 4-percent plutonium oxide (of which 94 percent is Pu-239) and the rest is depleted uranium oxide.

Commercial nuclear fuel starts as uranium oxide. What many people do not know, Mastilovic said, is that plutonium is a normal byproduct in nuclear reactors that fission uranium.

Plutonium builds up in the fuel inside the reactors and eventually provides up to 40 percent of the core's heat energy. Fission of plutonium produces this energy in the reactor at the end of the life of the fuel.

"We're not introducing a new element to a core, plutonium is already there," he said.

And he also noted that "we're not changing the thermal output of the reactor."

Mastilovic said that while Pu-239 is more energetic than U-235, "The license governs the use of MOX. Heat inside a core can be managed by blending different fuels just like mixing different types of wood in a fireplace."

Oak Ridge National Laboratory data presented by TVA to the Nuclear Waste Technology Review Board show little difference in decay heat loads between used MOX fuel and normal non-MOX fuel.

"Thus the difference in heat load between used MOX and used uranium oxide fuel can be accommodated in spent fuel pool cooling or space requirements and in dry cask thermal design," Mastilovic said.

Next steps

Overall, with TVA support as a cooperating agency, the DOE is on track to complete a supplemental environmental impact statement for MOX fuel use that will assess safety for workers, the public, and the environment. TVA's public affairs office told ANS Nuclear Cafe that the MOX program will proceed in phases with multiple opportunities for public input.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission licenses for all the reactors that are candidates to use MOX will have to be updated to address physical operating differences and any changes in safety requirements. Technically, at this point, TVA believes that the physical modifications needed for each reactor are manageable. Also, TVA expects the DOE's MOX to cost less than uranium fuel.

A decision to proceed with engineering and licensing is currently expected to be made in 2013.

_____________

Dan Yurman publishes Idaho Samizdat, a blog about nuclear energy, and is a frequent contributor to ANS Nuclear Cafe.