What a difference a prime minister makes

Japan's new political leadership represents a sea change in the post-Fukushima era

Want to know what the difference is between the current Japanese prime minister relative to his predecessor? The answer is how he deals with the issue of nuclear energy and blame for the ways TEPCO and the government contributed to the Fukushima crisis.

Former PM Naoto Kan threw a temper tantrum in the TEPCO emergency center and in a statement that loosely translates as "off with their heads," called for the permanent closure of all the nation's nuclear reactors.

Current PM Yoshihiko Noda accepts that the government and TEPCO made serious mistakes, but says that the country can do better and he is committed to restarting the nation's 54 reactors, which provide 30 percent of Japan's electricity. He also must reverse the nose dive the country's economy has taken and rebuild the communities shattered by the earthquake and tsunami.

Want third-party confirmation of that? Check out a major paper by James Acton and Mark Hibbs titled, "Preventing Another Fukushima." The paper puts its lead emphasis on the need for an independent nuclear safety agency, something Japan didn't have on March 11, 2011.

Nothing outside our imagination

Perhaps most important is the change in Japan's world view when it comes to nuclear energy. It is that nothing is outside the possibility of imagination.

Prior to March 11, TEPCO repeatedly and negligently rejected sound technical advice about protecting its coastal reactors from tsunami and earthquakes, saying such disasters were "outside its imagination." That's no longer the case under PM Noda.

In a press conference held last week PM Noda said, "We can no longer make the excuse that what was unpredictable and outside our imagination has happened. Crisis management requires us to imagine what may be outside our imagination."

In making this statement, Noda is acknowledging that the government shares the blame in part because its safety regulators and business leaders were "blinded" by the "false belief" in the country's technological mastery.

"The government, operator, and academic world were all too steeped in a safety myth. Everybody must share the pain of responsibility," Noda said.

Restarting Japan's reactors

In laying out the view that there is no haven from accountability, Noda also is setting the stage for restart of the nation's reactors. As of March 13, 52 of the 54 reactors are closed and the other two will close in April.

The economic effects are already cascading across the nation, with its first trade deficit in 30 years and a highly annoyed steel industry threatening to go offshore with production if the electricity from the reactors isn't restored and soon.

Japan is less than 50-percent self sufficient on food production. This means that its high value heavy industrial exports, which require lots of electricity, are what keep its balance of payments from going in the red. Pull the plug on manufacturing exports and you've also yanked the rug out from under the economy. The key to all this is electricity, and with 30 percent of it coming from nuclear reactors, they can't stay turned off for long.

Noda has committed to convincing provincial government officials to agree to the restart of the reactors. That will be a tough sell. In fact, the provincial government in Fukushima province is so hard over about the impact of the reactor crisis there that it wants the government to scrap the four undamaged reactors at the Fukushima Daini site. There is, of course, the delusional policy of his predecessor, PM Kan, who wanted all the reactors off right away. Japan is paying for that folly with huge bills for fossil fuel imports. It can ill afford to sustain that kind of buying spree.

Kan comes in for a roasting

PM Noda may have painted the word "accountability" with a broad brush, but various groups looking into the Fukushima crisis have a narrower focus. In particular, the Rebuild Japan Initiative Foundation (RJIF) has issued a 400-page report. In searing language, especially for face-saving Japan, the group wrote:

"Top government officials without expert knowledge and experience ordered haphazard countermeasures," and . . . "orders from the prime minister's office may have raised the risk of creating unnecessary confusion and worsened the accident further."

The RJIF report leaves no doubt how hard the criticism is on the government and TEPCO.

"The emerging crisis at the plant was complex, and, to make matters worse, it was exacerbated by communication gaps between the government and the nuclear industry.

These players were thoroughly unprepared on almost every level for the cascading nuclear disaster. This lack of preparation was caused, in part, by a public myth of absolute safety that nuclear power proponents had nurtured over decades and was aggravated by dysfunction within and between government agencies and Tepco, particularly in regard to political leadership and crisis management.

The investigation also found that the tsunami that began the nuclear disaster could and should have been anticipated and that ambiguity about the roles of public and private institutions in such a crisis was a factor in the poor response at Fukushima."

The report's findings are based on interviews with over 300 government and nuclear industry leaders. One of the key findings is that trust between the prime minister's office and the Nuclear Industrial Safety Agency evaporated when hydrogen explosions took place at three of the Fukushima reactors. At that point the prime minister's office took matters into its own hands, bypassing the safety agency. The report says that PM Kan "aggravated the situation" through micromanagement.

There are three other commissions investigating the Fukushima crisis. One of them, from the Japanese parliament, has subpoena power. What hasn't been raised so far is whether or not charges of criminal negligence will be filed against TEPCO officials and some in the government. That may come in time from a panel being run by the Japanese parliament.

Kan's legacy a drag on progress

PM Kan's chief spokesman during the crisis, Yukio Edano, is now the head of the METI agency, which still houses the Nuclear Industrial Safety Agency. He's been a proponent of going slow in terms of restarting the reactors. Progress to reform the nuclear safety agency by making it independent have also dragged on. Rebuilding public confidence in restarting the reactors will require a thoroughly independent nuclear regulatory agency. The cabinet has approved a legislative package, but whether it will go anyway remains a question.

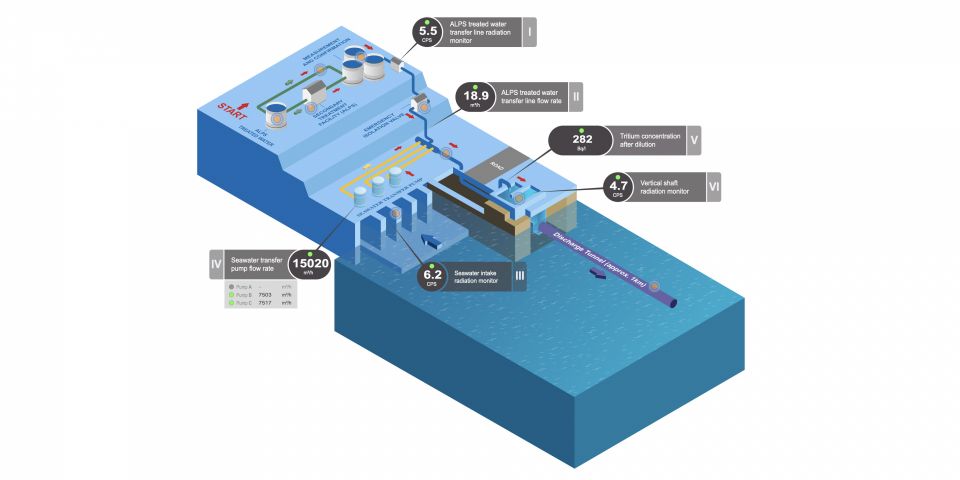

On the other hand, the current government manager of the Fukushima crisis, Goshi Hoshano, is a realist and has pushed back on Edano's defense of his former boss's policy of permanent shut down of the nation's reactors. He's pushed for safe decommissioning of the damaged Fukushima reactors and control of the huge volumes of radioactive water on the site.

The fact that Kan is out of power and Noda is in charge may be the real difference in getting the commercial reactors back in operation. That doesn't mean it will happen quickly or without a lot of political arm wrestling. Reuters reported on March 14 that 80 percent of those responding to a newspaper poll did not trust the government's promises of improved safety for the nation's nuclear reactors.

Kan is under fierce attack for his failings during the crisis, but that doesn't translate into support for restart. The real challenge the government faces is to close the gap between deep public skepticism about nuclear power in general, which was created because of the "myths" of nuclear safety that pervaded the halls of power prior to March 11.

_____________

Dan Yurman publishes Idaho Samizdat, a blog about nuclear energy, and is a frequent contributor to ANS Nuclear Cafe.

.jpg)